Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich

Hollywood studios used to have their own genres. The ones they excelled at. For Universal it was horror; for RKO, film noir; MGM had its musicals and Disney, its animation. Nowadays, there are independent production companies which focus on specific genres, the way Blumhouse has for horror.

If Netflix has a keynote genre, it’s the longform docu-series. Ever since Making a Murderer became a sensation one Christmas five years ago, Netflix have scored successive hits with this format. And the format is so recognisable as to be almost a house style. Drone shots, to camera interviews, tense music on the soundtrack – if you watch with the captions on, it’ll actually read ‘[tense music]’. Did I mention drone shots? There are so many drone shots that in one show one of the drone shots caught another drone passing as it did a drone shot. The subject matter is what you get if Jerry Springer read a book. Terrible people doing terrible things. Terrible people doing terrible things to each other; terrible people doing terrible things to tigers; Ted Bundy doing terrible things to people; terrible people doing terrible things to children.

And so we come to Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich, Lisa Bryant’s new Netflix series based on James Patterson and John Connolly’s book. I watched – correction I binged – the show as protesters demonstrated against police brutality and the police responded with brutality and the President declared himself anti- the anti-fascists. All things normal: the new new normal. If you don’t know who Epstein was, he was like Gordon Gecko had fucked Gary Glitter. A Jordan Belfort type who faked his way into billions through lying, dodgy financial deals and buddying up with some of the richest most powerful men in the world. And yet with all this money, all this world open to him, a Jay Gatsby glamour, his main pleasure was the abuse, molestation and rape of young girls and women.

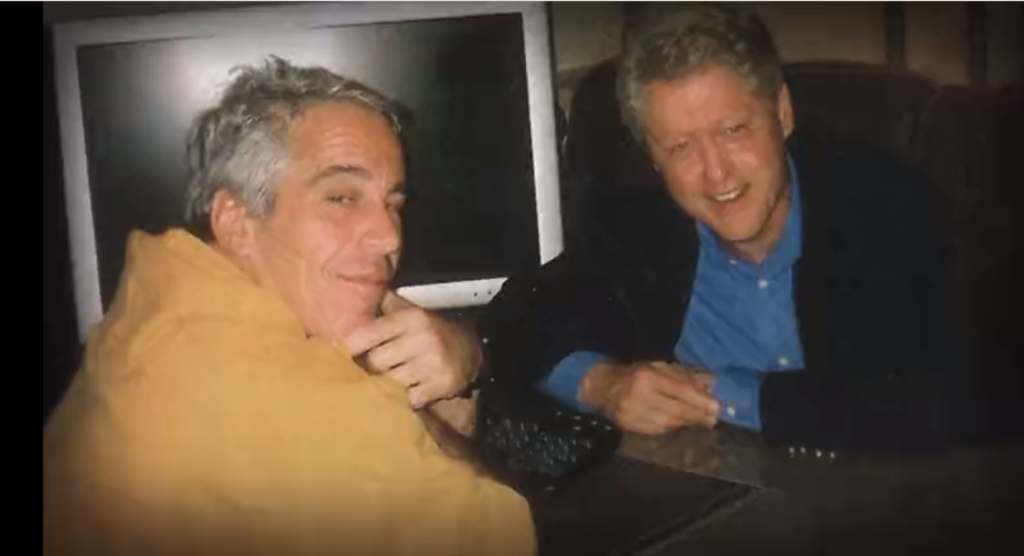

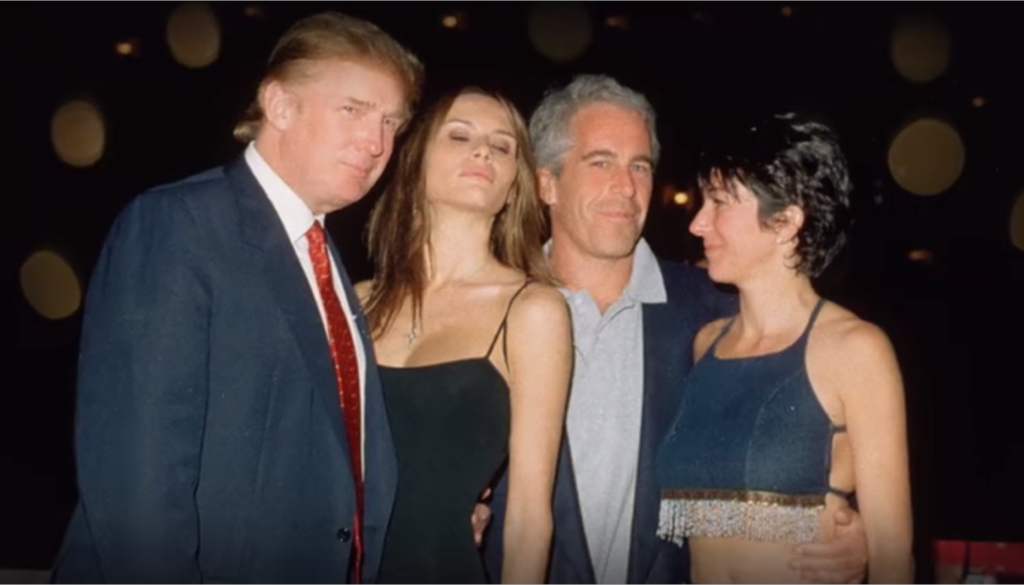

Epstein and people who were “never his friends“

Above, left: with Harvey Weinstein. Above, right: with Prince Andrew

Below, left: with Bill Clinton. Below right: posing with Donald Trump

Repeated symbols of his emptiness can be seen in his residences: one of the few questions he doesn’t plead the fifth on during a filmed deposition. He has a ranch in New Mexico, an apartment in Paris, a town house in New York and a mansion on Palm Beach. This latter is a blindingly white structure, with a turquoise pool and emerald lawns. Inside the walls are hung with female nudes, some arty, some black and white erotica, others that look like holiday snaps. This could be the man himself. Dully, implacably white but with intestines full of porn and a massage table where his heart should be.

As with the recent Ted Bundy: Falling for a Killer documentary (on Amazon Prime), Bryant keeps her focus on the victims and their stories of being recruited, manipulated and abused. This is an appropriate ethical choice, given the silencing of victims and the move to give them a voice in the #MeToo era, but it’s also a good choice from the point of interest. The big mistake that we make with assholes is thinking they’re fascinating. Be they serial killers or totalitarian dictators, or disgraced Hollywood producers, the mystique that surrounds terrible people is bafflingly persistent. Hannah Ardendt might warn us about the banality of evil; TS Eliot wrote about the Hollow Men and with Iago, Shakespeare gave us one of the best portraits of motiveless spite. But still there’s the faux mystery we have to plumb. Even the phrase ‘toxic masculinity’ has become through its winding evolutions something that doesn’t effectively describe what it seeks to describe.

This mystery is also self-serving. If we pretend that men who do such terrible things are such an aberration that we stroke our chins and look perplexed, then we let the rest of society off the hook. There were hundreds of Eichmanns; maybe thousands. And as for Epstein, there were hundreds of facilitators: from the staff he employed, the lawyers like Alan Dershowitz who for all his high rolling clients doesn’t seem to be able to clean his teeth to his alleged partner in crime Ghislaine Maxwell.

And what about us as an audience? Glomming on to the latest Netflix served horror. Are these exposés revealing something to us that we don’t already know? Are they filling the gap of an imperfect justice system which has either got the wrong man – Steven Avery – or the right man too late, as in Epstein? In the case of Andrew Jarecki’s The Jinx: The Life and Deaths of Robert Durst, the show led directly to the arrest of its subject. So, yes I guess they do have a role to play beyond sating our appetite for the parade of human awfulness. Plus, there is a big difference between knowing something and – as Slavoj Zizek is fond of telling us – knowing that we know something.