Programme overview: Vienna Shorts Austrian Competition 1 – The Eye Unlocked

The Covid-19 outbreak is a once-in-a-lifetime-type of event, and the same could be said about the world-wide imposed lockdowns as the neccesary response. The cause and consequences emerged as topics of many films produced in the past year, and which found it place on the festival circuit. In 2021, as the lockdowns were multiplying, the initial emotions and movie-making reactions got more eloquent, and films inspired by our new reality managed to find their niche not only in festivals’ special segments, but also in main competitions. That is certainly the case with the first slot of the national competition at this year’s edition of Vienna Shorts, subtitled The Eye Unlocked and consisting of the short documentaries and experimental works, emphasizing on the contrast of more and more insight possibilities getting unlocked, while people (still) being in the physical lockdown.

For the two clearly experimental films out of seven that were selected for The Eye Unlocked segment, the lockdown is not actually addressed, but is nevertheless present in the metaphorical context. Both of those films, NO1’s ROTOЯ | Sonic Body and Paul Wenninger’s O are powered by rotation. In the former, it is a mechanical construction resembling a loudspeaker that is rotating, the rotation on the visual level is perfectly matched with loops on the auditive level taking their cue and following the pace perfectly. As the construction gets more and more skeletal in its representation, the auditive component becomes richer and the viewer falls down to a hypnotized state of mind. In the latter film, its filmmaker and protagonist himself is the very axis of the rotation, while the room and the flat around him is rotating, experiencing changes over time. His fixed position and the changes in the space serve as a clear, albeit simplistic, metaphor of the lockdown and house projects undertaken to fill the time.

Two more films blur the line between the experimental, documentary and visual arts. Antoinette Zwirchmayr’s Oceano Mare takes Alessandro Baricco’s eponymous 1993 novel as the source of inspiration in order to make an artistic installation in a space between the abstract and the concrete consisting of rocky beaches, woods, shores and bodies of water in which the naked human bodies (belonging to young women) are exposed and shot in 16mm, in colour and without any sound. The dotty structures of lens filters invite us to connect the dots ourselves. Another artful work is a combined effort by the filmmaker Nigel Gavus and the artist İlkin Beste Çırak. In their short Letters from a Window, they join the beautiful black and white photographic and video material with the narration of the titular letters that are quite sincere and heart-felt, offering a deep insight into the mind, memories, hopes and associations of a person whose complete life was put on a break. It is one of the shorts that simply needs to be seen and felt.

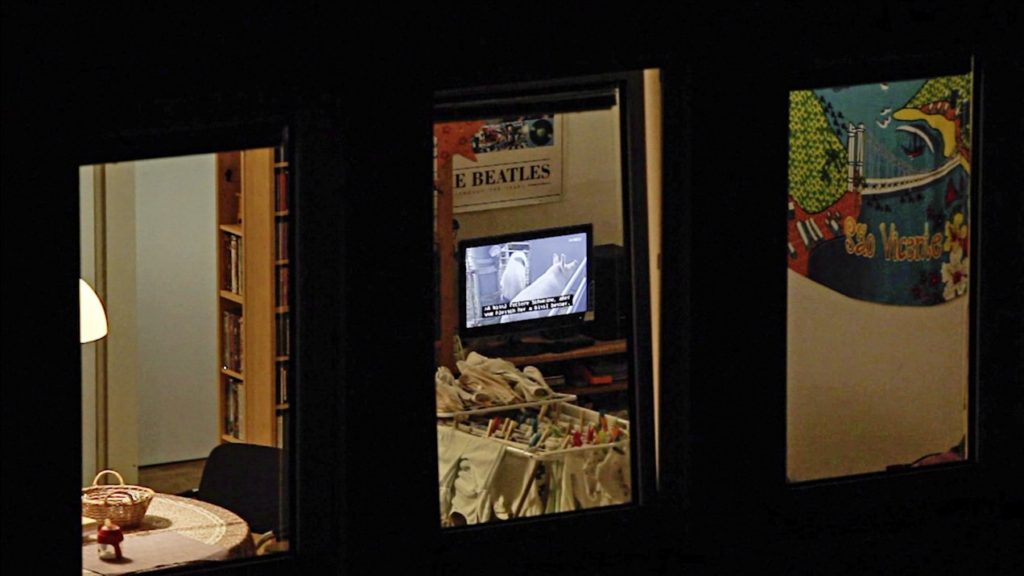

The remaining three documentaries address the topic of the lockdown in a direct fashion. Two of them complement each other at least on the surface, since they are covering the opposite aspects of the same thing. While Katharina Pichler’s Feirtage is set on the streets of Graz during the daytime, Michael Heindl’s Spring Will Not Be Televised prowls into Viennese apartments in the night time. Common thing for both of the films is their time frame: spring 2020 and the first lockdown, but it shows it different faces. Freirtage is largely devoid of human presence (there would be an occasional passer-by, caught from afar), sounds of nature and the automated sounds of the city life (from church bells to the emergency sirens) take over the soundscape, and the whole film functions as a document of time standing still, even for a brief period. For Spring Will Not Be Televised, human presence is essential since Heindl is a keen and occasionally humorous observer of the human behaviour, at least one particular habit – TV-watching. News dominate the TV menu, and the pandemic event dominates the news, but, as the “study” progresses, the programme gets more and more relaxed. Heindl does not break the trust of his subjects, efficiently creating an illusion of filming them from the outside, while occasionally breaking the cycle of the TV-screens in the frame by widening the scope to the whole buildings.

“Letters from a Window” by Nigel Gavus and İlkin Beste Çırak. Courtesy of Six Pack

“Spring Will not be Televised” by Michael Heindl. Courtesy of Viennale

Probably the most accomplished title in this slot would be Christoph Schwarz’ Civilization. For its 23 minutes of runtime, it is a double-topic autobiographical documentary, equally the story about an artist in peril during the pandemic left with children in his family home in Carinthia while his “essential worker” wife has to go to work in Vienna, and the story of addiction. The object of his addiction is the titular cult computer game, and, to be precise – its first issue from 1991. How can be a computer game from the era of 386s be played at all in the era of MacBooks? Easily, via the online emulator. How can it be so addictive, especially for the people who played it a while ago and rediscovered it? Well, in the time of lockdown, everybody needs a hobby and playing an old computer game is as legitimate as becoming a serial baker or cooking the ridiculous amounts of jam, for instance. The difference being all the bread, the pastry and jam would be eaten eventually, while the time spent playing a game is not coming back. Schwartz deftly shows how an addiction creeps into a regular daily life and overtakes a person, resulting in the quite contemporary way to deal with things, through a support group via zoom, revealing the wounds and gaping holes the lockdown left in our psyche.