Destination Unknown

Chapter 5 of the Fido Fiction & Documentary International Competition

“We’re covering long distances in this program”, say Doris Bauer and Marija Milovanovic in the introduction of Destination Unknown, the fifth strand of Vienna Shorts’ Fido Fiction & Documentary International Competition. The phrase is both literal, referring to the different parts of the world explored in the five films, and symbolic, unintentionally gaining additional meaning as the whole festival’s lineup gains wider national access by viewers through the web.

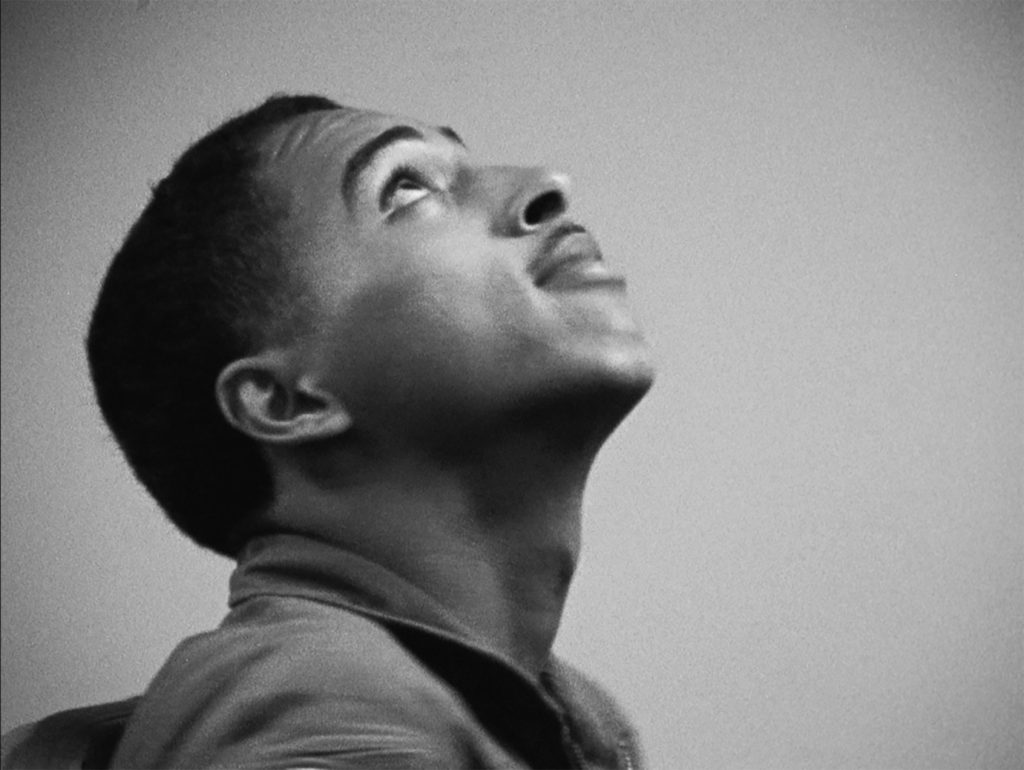

The distances are often physical, but sometimes also a matter of the mind, as seen in Recovery (USA 2020), a short directed by Kevin Jerome Everson. This American competition entry is a mere ten minutes long, but feels longer, on purpose: it is an endurance test for the subject, and for us. Filmed in real time, in a single, static shot, this black-and-white documentary follows the experience of a trainee submitting to an aptitude test at the Columbus Air Force Base. As he follows a series of repetitive instructions, the static camera still manages to close in tighter on his face, creating a sense of claustrophobia that is enhanced by the 4:3 format (this is one of three films of the program opting for such kind of aesthetic).

While ostensibly a two-hander, the film limits the instructor’s presence to an off-screen voice, delivering commands in a detached, clinical manner. The trainee’s responses are equally unemotional, even as the test becomes more physically demanding and gives the formal stillness a subtly nightmarish quality, an element that is pretty much constant throughout this strand of the competition (only the second short, while dealing with dreams and aspirations, chooses not to let that bleed into the visuals).

Dreams of flying are also present in documentary short: Mars, Oman (Belgium 2019) by Vanessa del Campo, which originally premiered at Visions du Réel last year but feels more current now, chiefly thanks to a sequence where two ÖWF representatives discuss the intricacies of space travel – the film focuses on an astronaut training in the desert – and one suggests that isolation is a way to liberate others, a light-hearted remark that feels very poignant at this specific point in time.

The visual link between Mars and the desert makes for some otherworldly imagery in a very grounded setting, and the cross-pollination is thematic too, in terms of the choice of local highlights, the generational difference in present-day Oman, and how tradition and progress are struggling to coexist. Meanwhile, the water keeps flowing to represent the flow of life, generating the single most charming image of the entire short: a breezy interlude where a young boy, still fully clothed, unwinds by bathing in an inflatable pool. Water is a recurring image, visually and spiritually, standing in sharp contrast to the oil that is still a coveted resource in the region.

Progress and tradition are similarly at odds in Monstruo Dios (Monster God, Argentina 2019), short by the Argentinian director Agustina San Martín. Here, ambiguity is a key ingredient, as it is never quite clear if the titular monster is an actual supernatural entity (the eerie closing shot explores that option with memorable minimalism), or just a way to describe the local power plant, an imposing facility that emits strange noises (when that happens, someone disappears, we’re told) and comes across as something alien, not quite part of this world.

Concerning God, the short toys with the notion in a playful manner, as Jesus himself is now part of the local music scene and inserted into song lyrics, juxtaposing a higher power with the very human, traditionally sinful, setting of discos and night life. Once again, it is not clear if there’s anything to it beyond the humorous association of visuals and sound, but that is entirely the point, as the ten minutes expire and we are left with deceptively simple and tight images haunting us.

South America returns in Sebastián Valencia Muñoz’ El Remanso (The Backwater, Colombia 2020). The title card itself is a declaration of intent, as the film’s name is written on a dilapidated sign one of the characters hits with rocks. Death imagery abounds as a family settles into an abandoned house that, much like a certain part of the country, has been left to die and yet appears to come back to life at night, haunting the living (especially the morally dubious father figure) with sights and objects from the past.

A cross shows up briefly, as a reminder of the spiritual stakes and, in a more irreverent manner, of the notion of a godforsaken location. There is still hope, embodied by the phrase “It’s almost dawn”, but overall the monster that is the future has laid waste to a piece of land and left it in a primal, desperate state. The blend of tradition and progress is once again at play, this time via the language that mixes local dialects with a more recognizable Spanish idiom.

The arrival of dawn is also at the center of the concluding film in this program, Dorian Jesper’s Sun Dog (Belgium/Russia 2020). It harkens back to the second short, only this time the desert is replaced by the Arctic and lofty aspirations make way for what is essentially a POV fever dream, rendered in tight 4:3 amidst empty houses and cheeky musings (the water imagery of the other film is distorted via a sight gag involving urine).

The dream-like quality is enhanced by the choice to capture this story on what is described within the short itself as the longest night in the world, and reaches its climax in the beautiful final shot, where the film effectively trails off towards the unknown. It is the literal embodiment of the program’s name, and the ideal grace note on which to end a journey that, in spite of the moniker, had a clear goal in sight and reached it numerous times throughout a subtly rich 80-minute journey.