Reflections 1

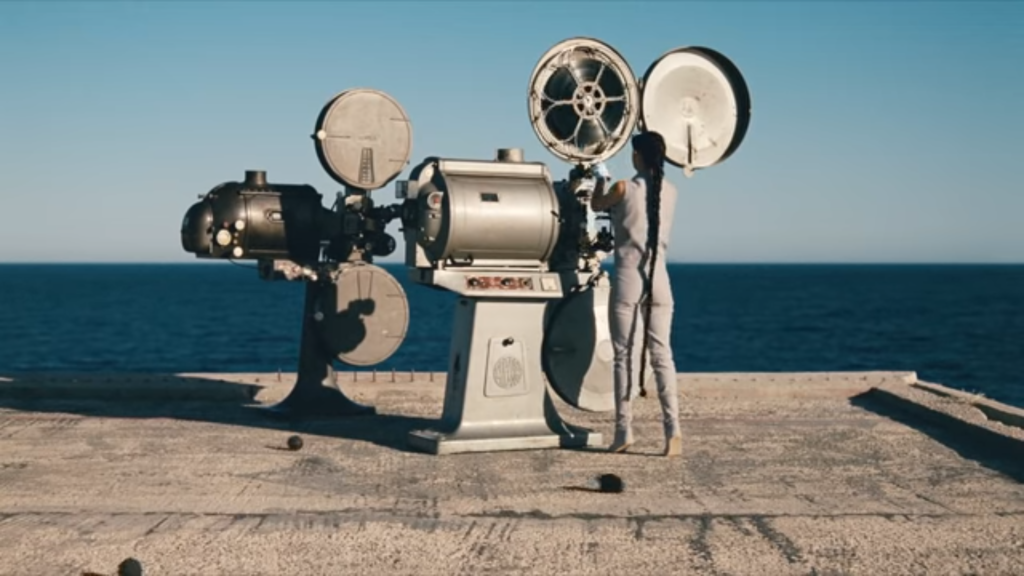

Two 35mm projectors, facing an ocean, have a tête-à-tête, awaiting, hoping someone will come. It’s time for changeover: the projectors need a projectionist. Someone comes, threads up the next reel, and keeps the movie playing. But without anyone else around, in this moment, that projectionist, whose white gloved hands literally hold the image, is also the screen.

Right now, we are all acting out the role of projectionist, operating whatever cinema-like (or not) viewing conditions we can in our various states of lockdown, all around the world. But with no one else around, just as Athina Rachel Tsangari astutely and prophetically shows in her short film, 24 Frames Per Century (2013), an homage to Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Mépris (Contempt, 1963), is that without the context of a wider audience, we alone hold the image and thus, are also the screen.

Projecting images (in this instance, digitally, and for me via television or laptop), I see more than the film I am streaming. I see my reflection. I cannot escape it. I see myself, not in or even on, but there, with the image, holding it in my reflection. I have become projectionist and screen, and the details are all wrong. I miss the cinema. The darkness, stillness, attentiveness, embodied otherness of the operator and apparatus, I miss masking most of all.

It’s an odd experience to ‘attend’ a film festival at home. Sure, it’s nice not to have to queue in the pouring rain, and I like that I can watch the film when it suits me (after its online premiere screening slot), but the intended embodied experience of 360 VR is flattened by YouTube, the ability to move within its sphere reduced to an up/down, left/right scrolling technique. We Are One: A Global Film Festival is the film industry’s version of Live Aid, free to watch but with donate buttons at the ready to raise money and hopes. I wonder if such an offering is enough and if it’s able to deliver anything that it promises: for whom does it even exist?

For industry it offers a talking point: a reminder and some clout for the festivals involved, a spattering of press coverage (even though many critics will have already seen the films on offer, jobbing journalists need something to write about), and an opportunity for artists to have their work seen, revisited, showcased, perhaps even elevated by mercy of participation. But the focus has shifted greatly from what an actual, physical festival offers – and not just interms of bodies and corporeal affect. There is, too, a shift in the positioning of our proximity to it, to each other, perhaps even to ourselves. The organisers know it, too. ‘International’ is replaced with ‘Global’ as there is nothing inter about an online experience; it spans but does not permeate. A film festival online places the films as items in front of us, but it cannot get into them. By virtue of extension, I believe, neither can we.

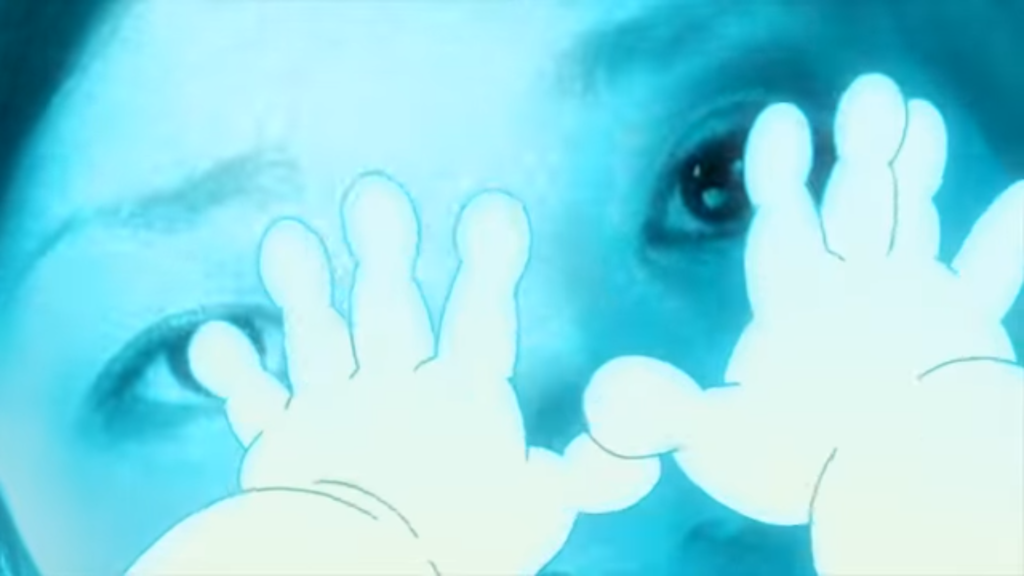

Instead, we become a surface. They reflect onto us and we reflect back, but there is nothing knotty in between. And while I am appreciative for the opportunity to watch great films – I especially loved watching Masaaki Yuasa’s Genius Party: Happy Machine (2007), a surreal yet poignant exploration of an infant’s experience, watched with and as close to through the eyes of my almost one-year-old infant son – from the comfort of my own home, in the wake of a world that feels as if perpetually on fire, it’s the knotty stuff that I value most and right now deeply miss.

I wonder, too, what sort of an audience is virtually attending this festival? It is less exclusive and certainly less expensive than the status-driven and economic realities of the physical festivals involved, and yet, not necessarily any more accessible. Do people outside of our industry know about it and how do they navigate its tone and tempo? Personally, I took a chance on things I wouldn’t usually entertain, and that I wouldn’t expect to, in return, entertain me. But, curious about the curatorial choices, and with the ability and confidence required to ‘walk-out’ now reduced to a thumb tap on a spacebar, I watched J-Pop sensation, Arashi, in their so-called Special Music Moment. A patchwork mini concert from their 2012, 2014 and 2017-18 tours, with a recorded intro from the young heartthrobs, it made me wonder what, if any, are the parameters and boundaries of categories like film, short film, documentary and festival. Arashi could be the winning act of a reality TV talent show.

America’s Got Talent (AGT) just started airing its 15th season on Netflix in the UK. The first few minutes address and betray the reality we are living in. The opening credits are set to a softly sung version of America’s national anthem, The Star Spangled Banner, as news footage presents the supposed ‘togetherness’, ‘heroes’, ‘giving’, ‘kindness’ and ‘solidarity’ ofa country under the strain of coronavirus. America has the highest COVID-19 infection and death rates in the world. The first ‘act’ is a White, heteronormative couple (dressed in red, white and denim blue) who have trained their self-proclaimed family of performing pigs and hogs. This new season of AGT sees its first all-White panel of judges for years, after Season 14 judge Gabrielle Union’s termination, following “her refusal to remain silent in the face of a toxic culture at AGT that included racist jokes, racist performances, sexual orientation discrimination, and excessive focus on female judges’ appearances, including race-related comments.” Black Lives Matter. Protests in the US, UK and elsewhere take place as the showairs. This weekend, AGT will probably be seen by many more viewers than We Are One’s scheduled short by a Black female filmmaker, Mati Diop’s Atlantiques (2009), and probably more than are watching her feature, Atlantics (2019) on the very same platform, owing to its homogenous algorithms. Not that YouTube’s are necessarily any better. But, finishing one film from the festival tends, at least, to lead to another from their programme – five days in, with more than I have time to watch, I don’t know where it leads someone who has finished viewing everything – I know I won’t see it all. That’s one thing that the physical and online festivals have in common, for me, anyway.

But perhaps what’s best about this festival is that it offers access to talks and people, as well as films. It was somehow reassuring to see filmmakers pop up onscreen to say a little something – surely one of the most attractive elements of attending film festivals is the talent and actual togetherness they invite. Postcards from Sarajevo Film Festival Friends offered this much needed glimpse of the artists upon whose labour the entire industry depends. From Aida Begić’s honest reflection that it was nice to have time “to think, to contemplate” before being “fed up” to Jasmila Žbanić’s hopefulness, “We change. Films will change, cinemas, festivals. We embrace new and unknown. It will be great if we do it with solidarity and love,”our current moment should be about togetherness and solidarity, but it needs the honesty and sincerity of art not algorithms. But above all else, what I miss are the in-between bits; when friends, colleagues, cafes and conversation follow and pre-empt screenings, where I would discover more about the work, lost in glorious, spacious thought. At home, I have laundry to do, dishes to clear and a child to teach and entertain.

Returning to and reflecting on Tsangari’s short film, 24 Frames Per Century, and the two projectors, taken out of context, I wonder how any of us might once again find our place in the world, and interpolate our societies with rich cultural intentions. The ‘pessimist’ projector, with its reel running out, is right to wonder, “What if nobody comes back?” But the‘optimist’ waits with a sense of assuredness, knowing that a film can only really exist if it is screened – the object implicit in its verb – and that, like the reflection of the lives we hope to see and be inspired by in cinema as art, “Somebody always comes back.”