Vienna Shorts’ “Nightmares”

The line dividing genre movies and “serious” filmmaking is now completely blurred, to the point that genre works are now being programmed by even the most highbrow film festivals (classical examples from the recent years would be Guillermo del Toro’s The Shape of Water or Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite). The line is even fuzzier when it comes to short films and shorts festivals. Boiled down, everything relates to know-how: the sets of skills needed for both genre and more serious filmmaking are quite similar, and the short film form is actually a concentrated showcase of these techniques. With a limited screen time, there is less space for the formulae often employed in features, so everything comes down to concept and execution: usually inspirational, original and therefore quite artistic.

The Late Night film section of Vienna Shorts has earned a reputation for intelligent programming and smart selection. Since this year’s edition is anything but ordinary, as it happens online, the task was even harder for curator Diana Mereoiu. Films selected for one of the three sections have also to work in less than ideal conditions, since online viewers will be viewing these films outside their natural home, which would be on a full-sized screen in a darkened cinema.

Judging by its poster section, Nightmares, the programming task has been achieved with flying colours. It is thematically tight, yet diverse enough when it comes to subjects and directors, screening new work by established auteurs like Jonathan Glazer and Peter Strickland alongside promising, up-and-coming talents. Nightmares come in different shapes and sizes of horror, from the cold, cerebral approach to the more visceral, emotional and personal

In the section’s most resonant film, Jonathan Glazer’s The Fall (2019), which comes six years after his groundbreaking feature Under the Skin(2013), the nightmare is rooted in reality but lifted to an abstract level. A mob consisting of people wearing masks gets their hands on an individual, also masked, and performs something that looks like a lynching with ritualistic undertones. It is certainly a nightmarish commentary on the state of the contemporary world, anthropologically potent, and masterfully coloured without any kind of dialogue and explanation, but expertly conveyed through the superbly detailed set and sound design as well as by Mica Levi’s pulsating, drumming score. It works on a universal level, as a nightmare everybody could have.

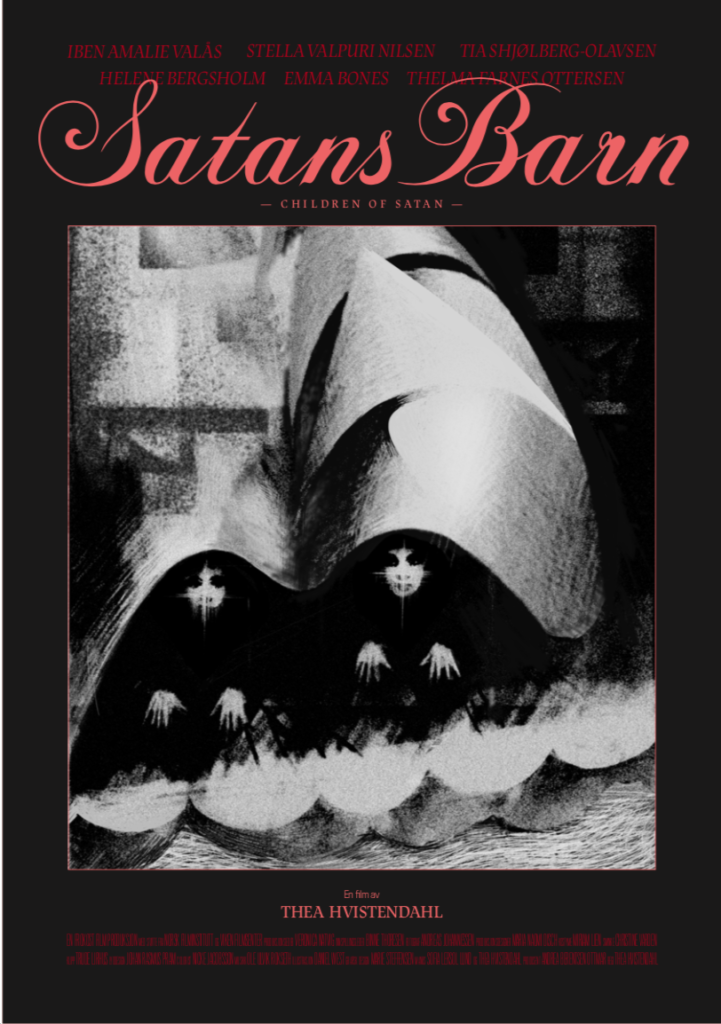

At the other end of the selection, there is Thea Hviestendahl’s Children of Satan (2019) that also touches on the themes of group mentality and individual outsiders. The programme’s longest film, clocking in at over 23 minutes, takes place at a Christian summer camp for girls, where two friends try to prove something by hurting the new girl. Shot in cold tones with some striking visuals highlights, notably a neon cross, and slow in tempo, Children of Satan feels like a study for a future feature film, or perhaps a feature re-edited down to the short form. This brevity is something of a burden for such a rich story.

Despite being confined to the claustrophobic setting of a car on a snowy road, Whiteout (2019), directed by Lance Edmands, speaks volumes about wider social issues. The leading couple’s already unpleasant ride, punctuated by bickering, is interrupted by a seemingly demented, shabbily dressed stranger standing on the road, or walking in small circles, who proves completely unresponsive to the couple’s attempt to either help him or get him out of their way. This unexpected situation divides the couple even further, with tragic consequences. As the director demonstrated in his earlier shorts and especially in his feature debut Bluebird (2013), his long-standing preoccupation is the relationship between individual behaviour and the wider impact this has on our immediate surroundings and society in general. This also holds true for Whiteout, a fine example of economical storytelling and perfectly placed, well executed plot twists.

Sticking with the theme of anti-social behaviour, Marcus Svanberg’s Killing Small Animals (2020) is a story of an addiction and the urge to “raise the stakes”. The unnamed protagonist, who lives alone in a secluded country house, commences her “journey” with killing a butterfly. After a period of cooling down, she develops more “creative” and brutal ways to kill bigger and bigger animals. As we know from serial killer flicks, this does not satisfy her needs and the question is for how long she can hide her bloodthirsty urges from society. With almost no dialogue, Svanberg has to use other means of expression, like the striking visuals of the vast outdoors environments contrasting with the austere look of the cramped and poorly lit indoor locations, and a neoclassical music score of gentle piano and orchestral strings to map the emotional state of his unhinged anti-heroine.

Oskar Lehemaa’s Bad Hair (2019) is also quite a personal nightmare fuelled by one individual’s unsatisfied urge to change his destiny. It starts with an issue that has been affecting men all over the world for ages: balding. For the protagonist the trouble starts with the shipment of a thick, black, slimy substance that can apparently make his hair grow again. The instruction manual is both graphic and written in a language he obviously does not speak. Once he botches his attempt to do everything as written and pictured, and the goo ends up in a place it was not supposed to, the film’s full-blown body horror kicks in, channeling raw gross-out elements before everything ends up in a fever-dream series of absurd accidents. Bad Hair might be too neat in the way it crosses the borders between the sub-genres, but Lehemaa uses visual, dramaturgical and sound design elements to create a sense of foreshadowing, which helps smooth the tonal shifts from psychological dramedy to horror to absurdist and occasionally brutal comedy of errors.

Sevgi Eker’s 49 Years from the House on the Left is another fine example of a fever dream: a story impossible to re-tell as a whole, shot in one take and on grainy 16mm film. An old man wants to contact a young boy’s grandmother, who he claims he knew in the past, but the dim lighting and discordant piano music interrupted only by distant thundering sounds create a nightmarish feeling where the real and the unreal blend. Maybe the opening quote by Jacques Lacan about the real being something that resists symbolization could serve as a guide for viewers trained to interpret reality through the symbols and coded meanings that cease to function in Eker’s film.

Finally, Cold Meridian (2020, WP) is another experimental foray by Peter Strickland following his last year’s Orizonti Corti title GUO4. It consists of 8mm and 16mm clips shot in a slightly boxy 5:3 aspect ratio. Part of the footage is sourced from a photo documentation of a choreography session for a dance piece that has not been performed yet. The dance itself, resembling a wrestling contest between two naked people, a man and a woman, is one level of the nightmare. The viewing of it, complete with narration that includes the viewers, is another.

Yes, nightmares come in different forms, more or less connected with reality, or what we see as such. The Nightmares section of the VIS Late Night programme examines them and their connotations in depth, serving the audience with some lasting impressions. The selection is diverse, brave and timely for the world in 2020, which more often than not resembles a nightmare.