The Year of the Discovery (2020), by Luis López Carrasco

A 200-minute-long documentary mainly consisting of talking heads (often several at the same time, on split-screen) discussing local politics and largely-forgotten events that took place almost 30 years ago in Cartagena, in the Spanish region of Murcia, may not be the most attractive pitch. Yet as soon as it world-premièred last January at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, Luis López Carrasco’s El año del descubrimiento (The Year of the Discovery) instantly became one of the most exciting films of the season, and as the months and game-changing events go by around the world, it has continued to prove one of the most relevant works of a convulsed year. The awards collected in its subsequent, forcibly virtual, festival tour keep confirming it: as of early June, these include Cinéma du Réel’s Grand Prix, Thessaloniki Documentary Festival’s Golden Alexander Film Forward award, and Jeonju’s Special Jury Prize.

In that now unthinkable collective experience of those first screenings in Rotterdam, the awe was palpable in the atmosphere. The richness and density of the project is such that it sparks endless, sometimes surprising, possibilities of reflection and connections, as the film exposes the often ignored interrelations between seemingly extremely local issues or provincial life stories, and much more global social, geopolitical and historical processes. Thus, as each spectator can observe, it offers a mirror for myriad developments in the most diverse places and times.

Let’s go back in time, like the film itself does. First, to the project’s inception, that the author, born in Murcia in 1981, traces back to the moment he came across an image of his region’s parliament building in flames in the midst of protests in 1992, and realised almost nobody around him –including those who were already adults at the time– even remembered the incident.

Back to 1992, one of the most symbolically-charged dates for Spain: as the country celebrated the 500th anniversary of the “discovery” of America (with all the imperialist triumphalism and provocation that implies for the Ibero-American world), it was also trying to secure its place among the European gang and the “first world” nations. To show it had left behind the dark days of Franco’s dictatorship and was no longer the poor relative, it organised two ostentatious events: the Olympic games in Barcelona, and the Universal Exhibition of Seville. And in the meantime, Murcia’s historic industrial fabric was being dismantled for the sake of globalisation and European directives, leading to massive layoffs and demonstrations… and a government house in fire.

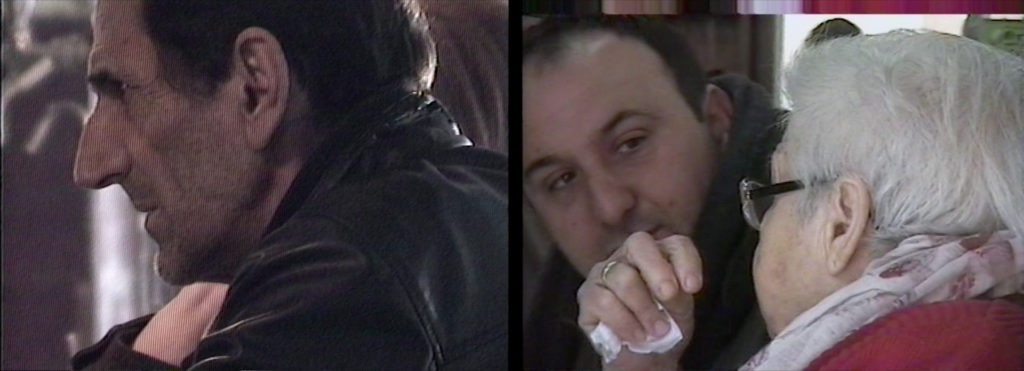

Now jump to 2018, when López Carrasco and his tiny crew gathered mainly working-class people from Cartagena in a local bar/café to speak of innumerable issues at different levels. The characters not only represent different generations (though they are predominantly young), with their diverse personal histories, but also reveal the huge gap(s) between the age groups, especially in the way they experience and understand society and work, and their role in both. Far from the social movementU+0073 and the union involvement of the early 90s, the youth of today grew up and started working in the hardships of a major financial crisis and imposed austerity measures. Activism and politics, for instance through trade unions, has become a luxury very few could afford in their precarious lives, and that eventually even fewer care about.

In the bar in which people chat, or at times talk directly to the camera in The Year of the Discovery, past and present coexist, and are voluntarily blurred together to show on the one hand how the past shaped the present, and on the other also how the present dangerously resembles that past. The Hi8 image (under Sara Gallego’s direction), as well as the entire production design and art work achieves the atemporal feel that makes it irrelevant whether we are in 1992, 2018, or any other year.

Luis López Carrasco previous (and first) individual feature film –aside from his work with the collective Los Hijos– already experimented with the aesthetic and atmospheric recreation of a crucial moment in Spain’s relatively recent political past. In El futuro (The Future, 2013), he staged a party celebrating the 1982 elections that brought the Socialist Party to power, on a night that Spain felt full of hope. In a way, his new film speaks of that party’s hangover.

The Year of the Discovery is mainly made up of the original footage in the bar, with often extremely close shots so we can virtually take part in the discussions amid the noise. But it also makes very efficient use of radio and television archive material, maps, text and infographics to illustrate and even to didactically explain the references in some discourses by the more informed participants (like well-dosed footnotes: enough not to get lost, but never overwhelming). Most of the time, the screen is split and used in varied ways, whether leaving one half black or juxtaposing images and often soundtracks; sometimes presenting two angles of a same conversation; others, opposing views from different generations. It is clear that we are dealing with more than one present, or more than one perspective. And that in the end, everything is connected.

One indication of the excellence of The Year of the Discovery is how its artistic and political relevance continues to live and grow even after it was finalised. Let’s jump again, this time to January 2020, at the time of its première… Even if I don’t remember it, I sure have lived it. (Aunque no lo reuerde sí que lo he vivido.) This is the first of three “episode” titles punctuating a film in which dreams are a recurring topic. In a way, it also describes the dreamy feeling of déjà-vu it provokes, and of how it may be talking about Cartagena in 1992 (and 2018), but speaks of so much more. For many of those first viewers, the predominant feeling after over three hours was of elation before the artistic experience, but of sadness, even depression, before the acknowledgment of failure of the collective organisation and of the working-class struggle.

For this writer, however, it acted as a soothing balm, as an antidote to the frustration and feeling of overwhelming impotence of the time (even though the film ends with a dream of impotence): over the previous months, popular uprisings had been bursting throughout the world, from Lebanon to Chile to Hong-Kong to Iraq, for very different and very similar reasons. Things were happening at such speed that, in our age of depthless social media journalism, it was hard not as much to keep up with the immediate facts, but to understand, reflect, compare views and go beyond the surface. And in the rush of a film festival, an intellectually ambitious yet utterly humble work offers you the occasion to sit back and finally take the time to listen for over three hours to real people’s analyses, testimonies, or simply their aspirations, opinions and life stories.

No one is preaching, no one has the final say. Some are outrageous (yes, nostalgia for Franco is still very much alive); others are heartbreaking, and a few even inspiring and encouraging. Altogether, they compose a complex, lively puzzle, that together with the critical perspective and scrutiny –so rare today– help understand. In this case, it mostly traces back the origins of the economic collapse of the region to concrete political decisions, often coming from Europe institutions. This may not explain the social struggles taking place at the turn of this year, though in some cases it offered concrete hints and obvious parallels. But in any case, it was a refreshing, rewarding and deeply moving mental and ethical exercise.

And it’s you the world eats. (Y el mundo te come a ti.) The second episode title speaks of how you may feel ready to take a bite of the world, only to be chewed up by reality. Fast forward a month and a half, to March, when The Year of the Discovery was to participate in its second festival (the International Competition of Cinéma du Réel, that it eventually won). The Parisian festival had to abruptly cancel its physical edition on its first day and go online A virus that until recently appeared to be a controllable, abstract menace, was now causing the world’s borders to close one after another, plunging us into a period of utter uncertainty, announcing an upcoming global economic recession and unrest; exposing the vulnerability of a worldwide interdependent structure based on globalisation and free trade and circulation; and proving the radical difference between societies with a strong safety net –exactly what most governments have been dismantling for over the past decades, often (especially in Europe) for the very reasons the film explores.

To burn down a parliament building. (Quemar un parlamento.) A final jump to the present, as this text is being published. Just a few days ago, as some regions of the world start to loosen their lockdown and others brace for catastrophe due to the disease that we thought would uncontestedly define 2020 in history, another major historical process has been unleashed. It has nothing to do with the virus that has already been bringing “normality” to its knees, but rather with the breaking point when normality can no longer be endured. The United States are not the centre of the world, but their weight in every aspect is such that major developments there undeniably affect the entire planet. And the reasons of the massive upheaval taking place there right now do and must affect the whole of humanity: the killing of George Floyd, yet another homicide of a black person by the police.

One image that so far illustrates the uprising in the wake of his death will certainly go down in history. It shows the Minneapolis police precinct in flames. A building symbolising power and its blindness to the pleas of a desperate people burning down, just like in the picture at the start of The Year of the Discovery. The question is whether the image of 2020 will be forgotten like the one of 1992.

The last title of the film is Epilogue, but that remains open.

Original title: El año del descubrimiento

Year: 2020

Runtime: 200’

Countries: Spain, Switzerland

Language: Spanish

Directed by: Luis López Carrasco

Written by: Luis López Carrasco, Raúl Liarte

Cinematography by: Sara Gallego

Editing by: Sergio Jiménez

Sound design by: Alberto Carlassare

Production design by: Víctor Colmenero

Produced by: Luis Ferrón Ferri, David Epiney

Production companies: Lacima Producciones, Alina Film