Reflections 3

I’ve been in lockdown for 119 days. But ‘lockdown’, as a concept, is forever changing; I can now meet friends in the park (from a safe distance), take my son to a local playground, and I can even get a (takeaway) cup of coffee from my favourite cafe, as restrictions ease. Cinemas are reopening, too. But ‘lockdown’ is not just a set of rules, it’s also become a state of mind. I’m nervous, now, about leaving the house. Partially, because other people’s behaviour is so wildly unpredictable – not everyone even believes there is a pandemic, as the hand written, graffitied and home printed signs warning of the evils of 5G, dotted about my neighbourhood, reveal – and, mostly, because I have new patterns of learnt behaviour that, like any ideology, must be unlearnt if I am to become fit for purpose in the wider world, a place that is increasingly difficult to square with the concept of society.

Courtesy of Il Cinema Ritrovato ©Lorenzo Burlando

This past fortnight, many have been in meetings at the virtual marché of what is still the world’s most prestigious film festival, announcing its selection and, to the world, that prestige remains more important than bums on seats and eyes on screens in our industry. Others have been drinking Aperol spritz in isolation, longing for the long, hot days and nitrate nights of Bologna’s Il Cinema Ritrovato, while the Neo-Baroque, Neo-Renaissance and Neo-Classicist buildings of Karlovy Vary sit, quietly stunning. I’m still in England; physically in Bristol, virtually in Sheffield, every now and then. Stuck in one place not because of poor WiFi, or even because of Brexit, but stuck as a state of mind that can’t and maybe just doesn’t want to move, yet, as I try to understand why exactly I chose to live in this ex-European land. Lockdown has marked the longest stretch I have spent in Bristol, in England, in the UK, since moving back here in 2015. It is only now I realise I spend most of my time here planning to be somewhere – anywhere? – else.

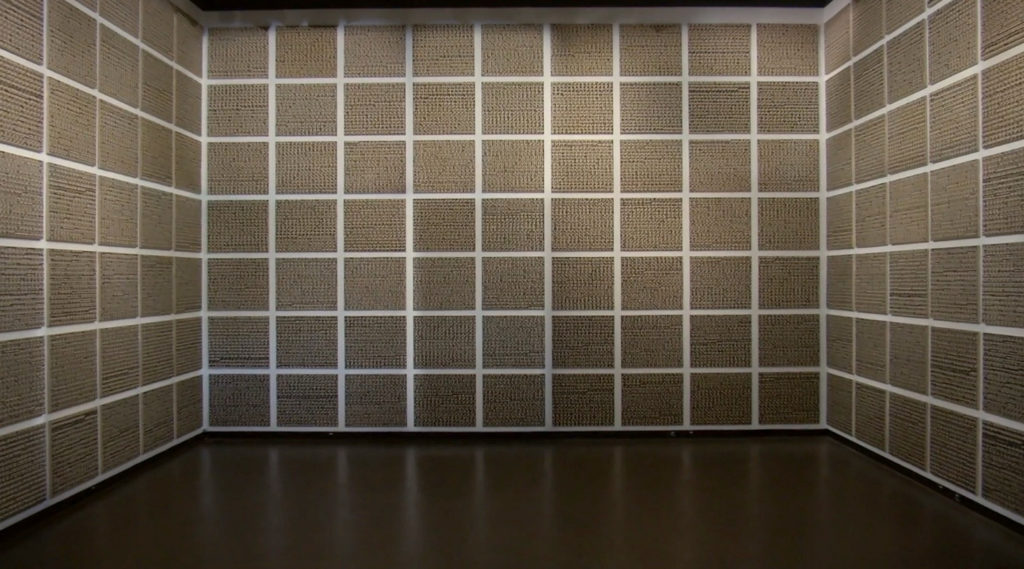

I don’t watch much, anymore; binge-watching makes me ache and devouring cinema like popcorn is too loud and too crunchy for my current disposition. But what I watch, I swim in, letting it sink into my bones, so that it can flow with the water that is already so much of me. This week I let Marsha Gordon and Louis Cherry’s All the Possibilities… Reflections on a Painting by Vernon Pratt (2019) flood in. The film is pleasing in its structural reflection of Pratt’s meticulous mind; exploring his All the Possibilities of Filling in Sixteenths, 256 panels of squares within squares within squares, the film’s run time is sixteen minutes and sixteen seconds, and it’s split into four parts (although not at four minute intervals and my maths isn’t good enough to work out if it’s otherwise significant where they do fall). Set to an up-tempo jazz score that feels improvised, but probably isn’t, the film, much like the art it animates, has a tremendous sense of movement; even the talking heads, and flat texture of the art when viewed through a static camera, have the appearance of art in motion.

Cinema affords us this appearance of movement, perhaps better than any other art form, something I am grateful for as I watch the squares in front of me dance to their jazz accompaniment while I sit, static, in my apartment, unable and unwilling to move. This sort of stubborn surrender is fine for viewing but there are aspects of our industry that need to be more dynamic, responsive even. In England, a major independent cinema in the country’s north, Tyneside Cinema, has harboured and covered up sexual abuse and bullying. Worse still, their appointment of an independent inquiry hasn’t been so independent at all. Continuing to ignore (and in some instances block) the workers who have suffered at the hands of both individual and systemic bullying and abuse, the message from powerful people is still a giant fuck you. It must suck, too, for the programmers, whose work is antithetical to the building in which it screens – de-colonising, deconstructing and redressing imbalances through global, cultural film. But that work, screened as it is, is for viewers to sit and watch, not for the organisation behind it all to respond to. How at odds our industry is. How desperately devastating.

Courtesy of Sheffield Doc|Fest

Further north, and across a soft but significant border, in Scotland, DIVE IN Cinema kicks off this week, a two-week online screening series that reminds us of the best our industry can do: bring people together. A co-programming initiative that therefore spans a wide range of form and content, DIVE IN is taking donations, which I’m pleased to write are not for the fledgling arts sector, but for asylum seekers, migrants and women in need. Watching people in the UK attempt to flood social media with images of themselves doing their jobs in the arts in the hopes that it would help petition government funding has produced mixed results. Yes, the government will commit funds (though we all know most of those will go to Theatre, capital T), but is the news really ‘good’ when it comes a day after that same government is fighting with their national health service about much needed money and resources?

Britain, though now stupidly on its own, watching European nations work together on a vaccine, is not the only place facing a future of cultural deprivation. But universities here are also in deep trouble, with one in my city proposing to close their Philosophy BA, despite it being a high quality and high performing degree programme. In my home country, Australia, fees for the humanities are doubling. In my home city, Melbourne, a second lockdown has started. Yes, the world is in a state of persistent crisis, but make no mistake, critical thought is also under attack.

Even the silver linings of lockdown are at risk of putting our freedoms in danger; working from home is a relief if your office politics distract you from the work that is your passion, but working from home also commodifies your so-called leisure time and space; access to international festivals you might never have attended due to the financial gap that a geographical one precipitates is awesome, but, if we do everything online, we might only ever be viewing, our option and our impetus to respond heavily reduced. What happens to the world when it is at our fingertips and eyeballs but nowhere else in our bodies?

Handwritten on the back on the panels, even Vernon Pratt would get fed up of All the Possibilities and go for a walk, sometimes. He was meticulous, sure, but he was also curious and worked with a sense of humour and amusement about the scale of the project he undertook. 65,536 possibilities are the ‘All’ of the thing, yet each square within the sixteenth had just two: positive and negative. There are many so-called possibilities when it comes to how to respond to something and, yet, for Tyneside, when you really boil it down, there are just two: to enable or to stop bullying and abuse. For critical thought there are many possibilities in determining how to look at a thing but there’s either space for the brain to imagine or there isn’t.

Pratt’s work is art, beauty, elegance, maths, science and more. He determined (the how of it, no one seems to know) that there are 1,025 shades of black and white that the human eye can discern. But there’s still just two that we see: black and white. So, as lockdown eases, there are many possibilities for the extent to which I remain locked down. And yet, no matter how many takeaway coffees I allow myself as I saunter off to the playground with my son in this so-called ‘new normal’, I still spend most of my day sat at home, knowing there are just two states of mind: positive and negative.