Review: Soviet Friendsbook (2020)

Imagine this. A kid in their “tweens” has a notebook. On each page of that notebook is a “profile” of a friend consisting of their answers to the kid’s questions, sometimes “spiced up” by a wise quote or decorated by their photo. Each question is a piece of an interesting puzzle. East European kids who grew up in the 20th century had such kind of notebooks towards the end of elementary school. It was not a part of the curriculum, it was basically THE Facebook of those times.

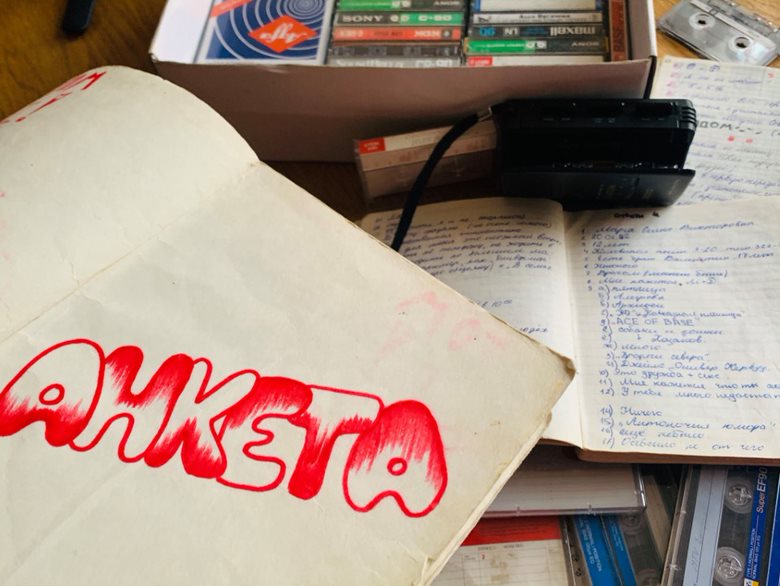

The notebook of that sort had different names in different countries and cultures. In Russian, it was called “Anketa”, meaning “Inquiry”. The filmmaker’s own “anketa” found in the countryside home of her parents sets the search in motion and asks some significant questions about a uniquely coloured, yet pretty much universal questions in Aljona Surzhikova’s documentary Soviet Friendsbook that was shown in not one, but two programs of Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival, Baltic Film Competition and KinoFF, the latter being dedicated to the cinema (and topics significant for) the post-Soviet countries.

Aljona (since she shares some of her childhood intimacy with us, I do not see the reason why we should not be on the first-name bases) was born in Tallinn, Estonia, then USSR in the early eighties in a Russian family. She attended the Russian-language school in the Tallinn neighbourhood of Lasnamäe, where she had a lot of friends and classmates. It was in the 90s, which were particularly turbulent not just in the terms of the shifts of the economic, political and popular culture, but also regarding the relationships between the nations inhabiting the former Soviet republics. The kids noticed it only partially, since they had more “important” things to worry about, but Aljona and her classmates were the first generation of the Estonian Russians to grow up in a completely different social climate than they were born into.

Lead by her “anketa” and some Facebook searches, Aljona sets on the mission to track down her classmates some twenty years later to ask them the same, but also some different, “grown-up” questions. Some of them stayed, like the class sportsman Roma, who became a “proper” Estonian police officer and who now works on the security detail of the country’s president. The others moved, some to the West, like the serious girl Yuliya, who is now a Waldorf teacher in Berlin, some to the East, like Masha, who is now a successful businesswoman in Russia. Some went abroad to achieve a material prosperity, like Vika who lives in Sweden with her Estonian husband and their three kids, others moved far away to achieve inner peace, like the class “tech guy” Stas, who now lives in Cambodia.

Surzhikova’s approach is quite simple, but also honest and deeply personal, which makes Soviet Friendsbook quite a pleasant and informative watch. Assuming also the role of the narrator, at one point she even admits that the whole film is a “friends-and-family” effort, with her husband (and former classmate) being the cinematographer and their children the travelling buddies. There is not much visual flare, which makes it more suitable for the small screens, but it does not feel like a completely run-of-the-mill work either. The home videos from the mid-90s are quite a nice touch, edited into the material by Surzhikova and Sergei Belik, while the graphics and animations by Irina Klimina and Lev Levitan suit the purpose when they are used to present Aljona’s friends and their current locations, but are a bit out of place when added onto the home photos.

However, the biggest value of Soviet Friendsbook is its informative side, allowing us to see Russian people who live in Estonia and their experiences in a new light. Surzhikova does not dig too deep into the politics and she surely does not poke the old wounds, but she dares enough to come forward and be up close and personal about her and her friends’ collective identities, as Estonian Russians, as the children of the Soviet Union and as the youth of the 90s, always in search of a better life. In the end, it is a unique and much needed viewing experience.

Original title: Anketa; Ankeet

Year: 2020

Runtime: 90’

Country: Estonia

Languages: Russian, English, Estonian

Directed by: Aljona Surzhikova

Written by: Aljona Surzhikova

Cinematography by: Sergei Trofimov

Editing by: Sergei Belik, Aljona Surzhikova

Music by: Anatoli Štšura

Sound design by: Dmitri Piibe

Animation by: Lev Levitan

Animation design by: Irina Klimina

Production company: Diafilm

Supported by: Eesti kultuurkapital, Eesti filmi instituut