Venice review: Godard seul le cinéma (2022)

There are few cinematic oeuvres more enjoyable than Jean-Luc Godard’s early 60s films. I love the self-aware mode, their air of casualness, their playfulness, the way they play around with cinematic forms while rarely losing our interest. His 60s output is arguably the most impressive single directorial decade in cinematic history. The problem with Godard’s work is that it’s almost too good, especially within contemporary French discourse, that it doesn’t allow for honest appraisal: this is the fatal flaw of Godard seul le cinéma, which is so busy to praise Godard the genius, that we barely get an idea of where his cinema sits within a larger context.

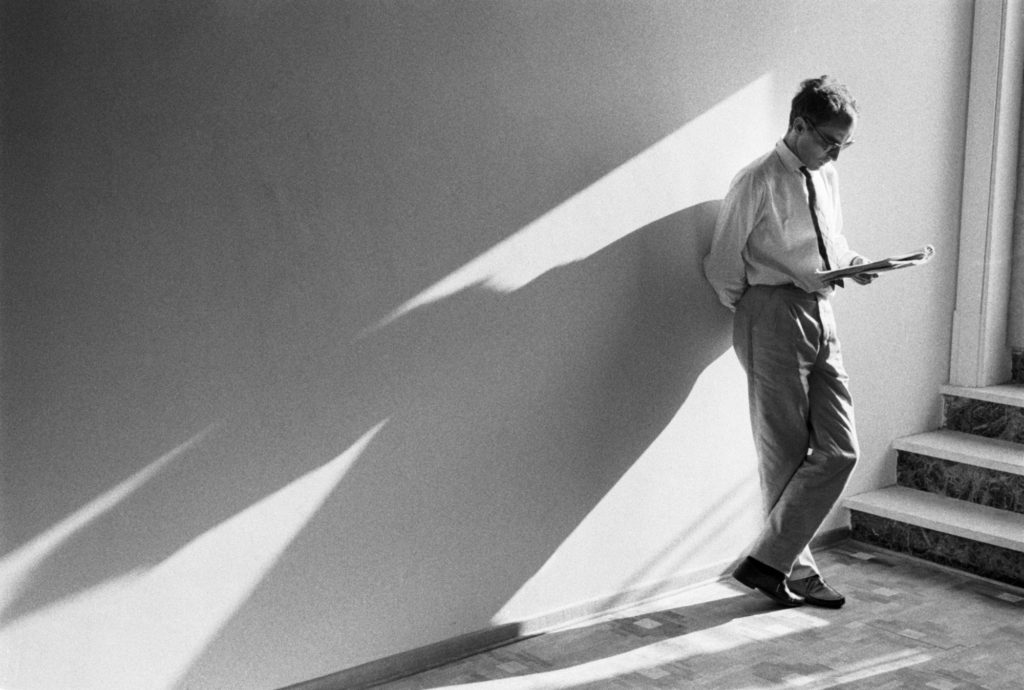

An impressive array of sociologists, film critics and biographers are put on the spotlight here, providing anecdotes and analysis that contrast with his actress contemporaries — women such as Macha Méril and Julie Delpy (while the men seem to have all passed away) — who give us an idea of life off-set. The film seeks to thread the line between Godard the man — taciturn, shy, erratic — and Godard the filmmaker, filled with brave gestures that would make a significant impact on the fabric of cinema itself. And while the personal details, from the way he would feed actors lines on set to his inability to foster healthy relationships outside of cinema, are interesting, the cinematic legacy of his works is bungled.

Godard himself doesn’t feature in the film. Neither do any filmmakers who were inspired by his work. But we are treated to a copious amount of clips from hisown films, ranging from Breathless to Le Mepris, to his explicitly political Dziga-Vertov period, to his epic video project Histoire(s) du cinéma. It certainly shows a man who was restlessly attempting to redefine cinematic language. It’s just a shame that the experts cited in this film, in their love for the filmmaker, are too breathless in their own appraisements to make for a more nuanced portrayal of Godard’s place within a larger cinematic canon.

We are told that no one had a run quite like Godard in the 1960s, either in terms of stylistic output or sheer relentless creativity. But cinema abounds with examples of mad, irrepressibly prolific creators, from Rainer Werner Fassbinder in the 60s and 70s to Takashi Miike today. Acknowledging other filmmakers doesn’t diminish Godard’s output; if anything it shows how he might have influenced others looking to make playful, politically pointed works with minimal budgets but tons of creativity.

Additionally, not only does the film misrepresent the French New Wave, which had already started with films by François Truffaut (like The 400 Blows, every bit as influential and innovative as Breathless) and Agnes Varda — and had some fantastic forebears in the form of Jean Vigo and Jean Renoir — but it fails to put Godard’s films within any larger French context whatsoever, making this documentary feel like a rather slipshod affair.

Even stranger is the diminishment of Hollywood cinema. It might be inconvenient to focus American at the expense of French cinema, but the influence of the Golden Age on Godard is simply undeniable. Godard, along with his friends at Cahiers Du Cinema, developed the auteur theory by looking mostly at Hollywood directors, men like Alfred Hitchcock, Robert Aldrich and Fritz Lang. And the pleasure of early Godard filmswas the way he took American forms and imbued them with a particularly playful Parisian spirit: for example, Breathless is literally about a man completely obsessed with the idea of Humphrey Bogart.

Additionally, as if to further stress Godard as a complete original, this documentary strangely elides the existence of Alphaville, a parody of American science-fiction and hardboiled cop stories that simply couldn’t have existedwithout prior influence. Acknowledging Godard’s love of American cinema (alongside his hatred of American imperialism) hardly diminishes the power of work. If anything it enhances it within a larger cinematic canon. A more nuanced film would have delved deeper into both these influences and those he inspired. Instead we are treated to a hagiographic take, presenting a rather flawed portrayal of the filmmaker at 24 frames a second.

Country: France

Language: French

Year: 2022

Runtime: 100′

Production: 10.7 productions (Cathy Palumbo) INA National Institute of Archives (Genevaux Anne) ARTE France (Verdier Nathalie)

Written/ Directed by: Cyril Leuthy

Cinematographer: Gertrude Baillot

Cast: Macha Meril, Thierry Jousse, Alain Bergala, Marina Vlady, Romain Goupil, David Faroult, Julie Delpy, Daniel Cohn Bendit, Gerard Martin, Nathalie Baye, Hanna Schygulla, Dominique Paini

Editor: Philippe Baillon, Cyril Leuthy

Music: Thomas Dappelo

Sound: Guillaume Valeix, Nicolas Paturle

Visual Effects: Silvain Bernard