Programme overview: Connected

Uppsala Short Film Festival

International Competition, slot 1

The first slot of the international competition of Uppsala Short Film Festival showcases a strong selection of films that explore the fragility of human existence within family and/ or society.

Lithuanian writer/ director/ animator Egle Mameniškyte competes with her graduation short Combing (2019), a 2D animation consisting of pencil drawings on paper that dig deep into her childhood memories for bonding moments with her father. She choses an unconvential way of approaching those brain snapshorts by using hair as a connector between the past and the now. This fine thread that pulls together memories and emotions dominates the film, and it transforms into such scenes showing her learning how to play the piano sitting in her father’s lap, or emersing into a child’s game together with him. It’s a contemplative jorney into director’s intimate world, a form of a curious, self-examining animated autoportrait that doesn’t give away what’s in Mameniškyte’s head or heart right now. And that’s its strongest quality, not counting the amazingly well done job by the foley artist/ sound designer Domynika Adomaityte in bringing the maximum out of tapes recorded in the author’s childhood and those recoreded by herself to click with the story and turn them into a magical time machine that effortesly travels from the past to the now, and back again.

Film still from “Combing”. Courtesy of Uppsala Short Film Festival

From “It’s All The Salt’s Fault”. Courtesy of Uppsala Short Film Festival

Another impressive animation that tackles the topic of a nuclear family is María Cristina Pérez González It’s All The Salt’s Fault, her third short film made in the hand-painted traditional animation technique, done in gouache on paper. Clever in its choice of a slot family instead of a human, the story is narrated by one of the daughters describing the atmosphere in the house against the backdrop of the armed conflict in Colombia. First she announces the profession of her father before starting to introduce the siblings and the mother to the viewer. The father, she explains, ẃas the military photographer who destroyed her first portrait as a five-year-old, because her smile “was too ugly”.

Humoresque but not comedic, It’s All The Salt’s Fault has all qualities of a well-thought multy layered drama that exposes the lightness with which the patriarchy claims its victims. The director is interested in situations that mutually impact members of one family and “about how we can go wild with the people we know the best, and who know us best”, according to her own words.

How one mother copes with her only son leaving the house to live with his wife (or to generally live his life) is taken on with much humor in Carmen Aumedes Mier’s short I’m Too Busy that plays on the documentary card, letting you clearly understand that it isn’t. The 12′ long voyage on Ocean’s (brilliant Ouyang Rongping) self-healing trip through Jitterbug – her son’s “field of expertise”, (at least according to the popularity of his YouTube channel) is a delightful watch. Ocean is observed in her daily routines, while voicing-over her own life in combination of self-reflective thoughts and little ironic remarks. In the mending process she discovers that teaching dance classes isn’t something that she enjoys doing anymore, and she becomes a dance student instead. That’s not the only positive change in her life, and home becomes the true place of comfort.

Carmen Aumedes Mier had only one month to create her film from beginning to end in a completely unknown environment, without proper casting and rehearsals. The shooting took place in Shangai during her exchange program over the film academy in Barcelona.

The distructive nature of machismo that goes hand in hand with violence is the inspiration for Silver or Lead, the short music commentary written and directed by the Colombian performance artist Nadia Granados. The word “commentary” is here consciencly used instead of “film”, because the song performed by Granados herself – playing a gangsta rapper – targets the wide-spread violence and its global acceptance in the society, helped by the media.

What happens when depression takes over, but it remains invisible for the immediate environment in which everybody’s preoccupied with their own lives? The directorial duo Jamil McGinnis & Pat Heywood doesn’t offer any answers, but they do raise this important question in Gramercy, their short drama that focuses on the inner world of a young man Shaq, who returns to his neighborhood after six months of absence.

Shaq’s state of mind switches from moments of relief to the depths of despair which is given in the switch between b/w & colour photography, or between the indoor and outdoor setting. Home is still a very grey place despite of fond memories of his family, and Shaq seems to be eager to spend more time outside the house when not trying to test the possibility of choking himself to death in the car.

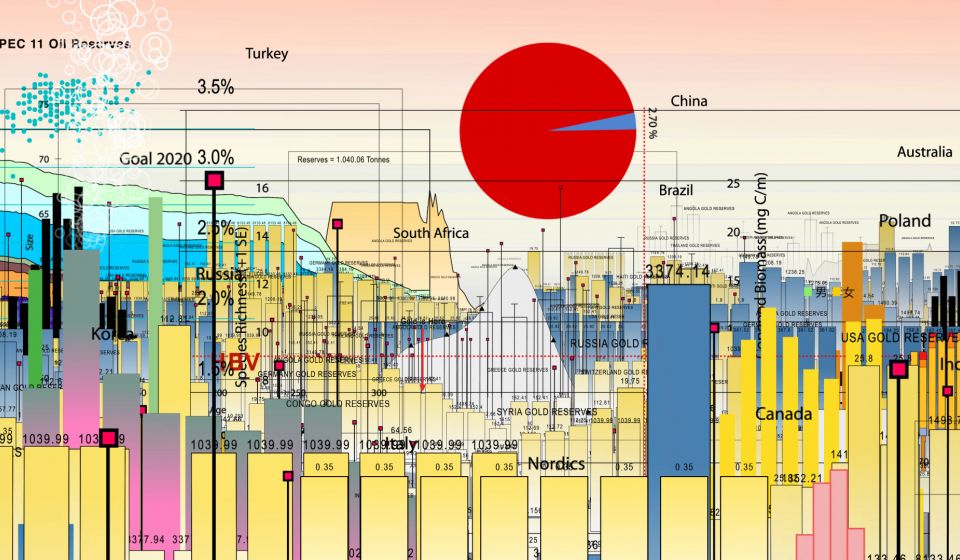

Happiness becomes all graphs and charts in Maja Gehrig’s hillarious animation Average Happiness, in which statistical diagrammes get transformed into sensitive bodies. Gehrig came to the idea through a misspelling she made in a proposal for another project, when she accidentally wrote “onaningram” (in German the verb “onanieren” means masturbating) instead of “organigram”. Therefore, all form of graphs, charts and diagrammes turn into living matter that grow together, push, hug or immerse into each other, creating a living, pulsating body. The climax is reached through the population pyramides.

The film is completely built on found footage from the internet which was put into a completely different context.

“The cities grow agains my spirit” chants an indigenous teacher to her class on one of their journeys into the nature. It is there the children are offered Ayalmasca, tea used since ancient times by the people inhabiting the Amazon who believe that the tea is able to purify body & soul, and “make the mind travel through and open communication to one’s ancestors.”

Fábio Baldo’s & Tico Dias’s mystery short The Fantastic Garden opens with this quote which becomes important to understand what happens in the course of film. Central to the story is the connection between the humans and the nature, and the devastating impact that the deforestation has on the Amazon.