Manlio Gomarasca: “Joe D’Amato was a one-man show”

Italian helmer Manlio Gomarasca dedicated his life to the genre cinema not just as the founder and editor-in-chief of the publication ‘Noturno Cinema’, but also as the festival advisor, programmer, curator and the author of books such as The little film library of horrors and Dario Argento: the image of fear.

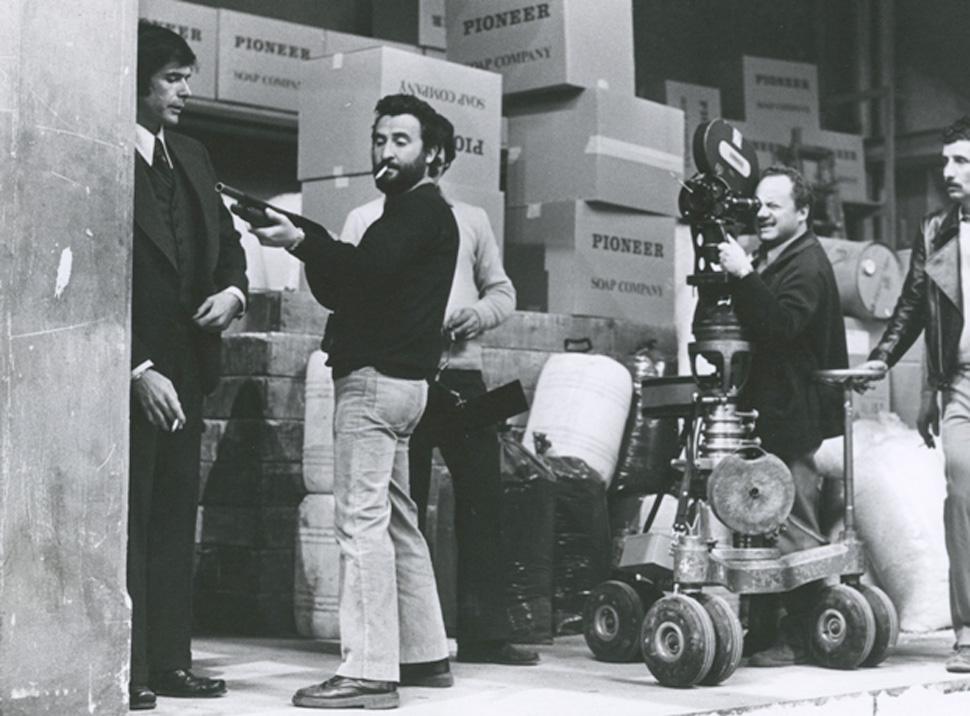

After ten shorts and one feature length documentary, Gomascara teams with Massimiliano Zanin to shed light on the Italian cinematographer, producer and director Aristide Massaccesi who built his career under the name Joe D’Amato (at the same time working under many other aliases). Their main effort is to shake off D’Amato’s image as the King of Porn, a label that destroyed his every attempt to be taken seriously as the film professional, and which made his comeback to what he liked the most – impossible.

Ubiquarian was at the premiere of Manlio Gomarasca & Massimiliano Zanin’s Inferno Rosso: Joe D’Amato sulla via dell’eccesso at Venice Film Festival where it was shown in the section Special Screening, and the film raised some questions. We met with both directors for a talk, but ended up speaking only to Gomarsca.

Who is Joe D’Amato for you?

It is very difficult to say, because he was many things. At the beginning, he was a DoP, then he became a director and producer before switching to making many other kinds of movies of different genres. He started with Spaghetti Western, he continued with war movies and then he went making sof core films which were still elegant, the horror, the sci-fi and the hard core which was really extreme.

What I really like about Joe D’Amato is his obsession with his work. He was constantly working, and for him the lifer meant being on the set, and do one movie after the other. You can always recognize – especially in the first stage of his career – the STAK??? He is very different from the other directors coming from the cinematography. He knew how to do everything alone. He was a one man show: he was behind the camera, he was the actor in his own movies as well as the DoP. You could see more on the screen than it was on the set.

Joe D’Amato’s movies were richer than the spectator is aware of. That’s what I like. The porn is another thing.

Maybe, but he also left a deep trace in that department.

That part of his career is something that he really didn’t care about. He was forced to do a pron movie again in the 1990s because his production company went bankrupt. I femmber that time because we were good friends. He wasn’t happy at all to be on the set of a porno movie. He shot 25 of them and when I was talking to him about that, he said: “I only do that to pretend to be making cinema again.”

Can you tell us something about Joe D’amato’s personal transformation, when he suddenly, towards the second half of his career started making movies unworthy of his beginnings?

He stopped doing horrors because of the market. He tried to have a comeback in 1991 with Ritorno dalla morte (Frankenstein 2000) and it was a total desaster. He produced the fore-last movie of Lucio Fulci (Door To Silence, 1993) and it was a flop. At that time it was extremely difficult to make another horror movie, and especially such type that D’Amato wanted to shoot. You mentioned his beginnings, and I guess then most famous film that he directed was Death Smiles on The Murderer (1974), but let’s not forget Antorpophagus (1980). At the end of his career before he died, he told me that he would like to make a new horror movie. He was trying to make a series and to produce it, but not to direct it as well. Unfortunately he died very soon after we spoke.

What was the most important thing you wanted to show about him in your movie?

Primarily to cancel the idea that Joe D’Amato was the king of the porn, because he was so much more. Secondly, I wanted to show his human aspect: he was an amazing man, nice and full of humour. Additionally, I wanted to point out at other type of movies he shot, and tell something about this story his obsession with the cinema. We are cinephiles, and this is what put us all together. So, we also wanted to explain how such love can kill you.

Were there any new things you learned about Joe D’Amato during the making of “Inferno Rosso”?

Lot of interviews were shot many years ago. Aristide died in 1999, and from the moment on, I interviewed many people around him. So, I am pretty sure that I know everything about him. But my focus was on the story of obsession, and we realized that it wasn’t necessary to talk about all movies he made but to try to find a red thread to tell this love story about one man and the cinema.

Speaking of which, Laura Gemser was ready to leave the nudity behind and became a close friend and collaborator, even beyond her acting career.

I am really sorry that we couldn’t put her in the documentary because of personal reasons. I did some interviews with her years back, and she is a sweet and shy person, so much different from the character she was playing. The relationship between Laura and Jo D’Amato was incredible because when her husband Gabriele Tinti died, she was totally depressed and she stopped acting, Aristide wanted her to be the part of the costume department, just to have her around him. On the set, everyone was family. All those people were a creative factory travelling the world with friends, making the movies together. It was something that was really important not only for him, but also for the rest of the film crew.

When did you shoot interviews with Joe D’Amato?

In 1998, so he actually never saw them. The others with his friends, producers, directors, and his daughter were done in different periods of time. Ruggero Deodato was a close friend, Lamberto Bava as well. All those people when they were making the movies in the 1970s were treated by film critics like tresh. Only through people like Tarantino, Rob Zombie and Eli Roth this opinion started changing. Joe D’Amato was never considered like the others because of the pornos.

Do you think that the opinion about him is slowly changing?

In my opinion, the time has come to re-evaluate his work. All the directors we mentioned before – they all did, and so did I watch the films which were different from the others. Nowadays we realize that movies made back in the 1960s and 1970s were free. They are important today because the cinema today is so different – there is less freedom than it that time.