In conversation with the helmers of “Seaguls Cut Through The Sky”, Mariana Bártolo and Guillermo García López

Mariana Bartolo ©Polina Korovina

Guillermo Garcia Lopez

Unlike the photography in our film, nothing in life is black and white

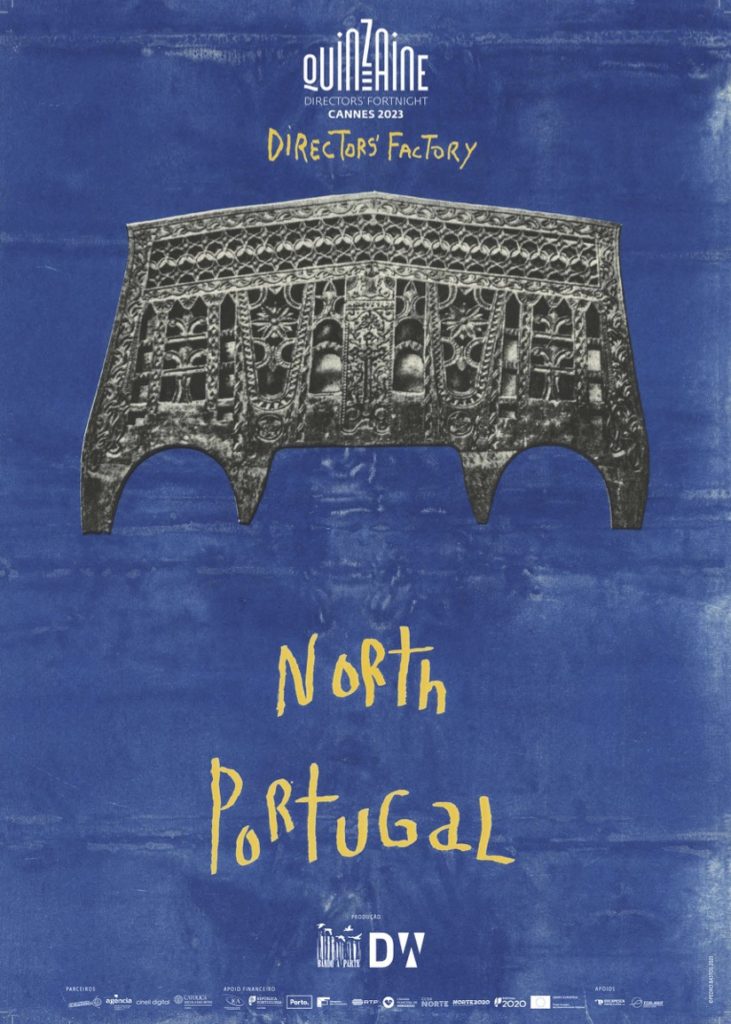

Ever since she had founded the production and consulting company DW in 2012, Dominique Welinski has been curating and producing the Factory program which opens Director’s Fortnight section in Cannes since 2013. The project was halted for a couple of years due to the pandemic, to be resurrected again in the festival’s 76th edition. Now back to life, Factory focuses on North Portugal with three short films done by mixed doubles consisting of young Portuguese filmmakers from the region, paired with their colleagues from Iran, Israel and Spain. The films were presented on May 17 in the packed Theatre de Croisette. On the Fortnight’s 2023 poster, the godmother of the Director’s Factory North Portugal project, and the famous Portuguese actress who acted in 19 Manoel de Oliveira’s films, challenges our vision.

Ubiquarian sat down to speak with the helmers of the black & white drama Seagulls Cut Through The Sky – Mariana Bártolo (Portugal) and Guillermo Garcia Lopez (Spain) at the Quinzaine Beach in Cannes, day after its world premiere.

Guillermo García Lopéz is a Madrid born and raised filmmaker whose first work, Frágil Equilibrio (2016), premiered at IDFA and won, among many other awards the Goya for Best Documentary. He is currently preparing his first fiction feature, Ciudad Sin Sueño, written at the Résidence de la Cinéfondation – Festival de Cannes, where it won the Moulin d’Andé CECI Award, and which was developed at the Berlinale Script Station and the Torino Film Lab. The setting of his film will be in the largest illegal settlement in Europe which happens to be at the outskirts of his hometown, and where he is creating a cinema school for young people. Lopez was awarded the prestigious Princess of Girona Award for Arts and Literature in 2020.

Mariana Bártolo is the Portuguese filmmaker, performer, and multimedia artist based in Berlin. She studied at Academy of Media Arts Cologne and graduated at Escola Superior de Dança Lisbon in 2008. Her shorts “Mansa” (2021) and “Whale Beards” (2021) screened Palm Springs Shortfest, Oberhausen, IndieLisboa, Osnabrück and Max Opüls Preis. She has been involved in various performance- and documentary productions, while also being emersed in photography, installations, and drawings. She is working on her new documentary At the table, and is collaborating in the development of the series Em banho maria and the intermedia project The loss of the night.

How was the selection process regarding who was going to work with whom?

GGL: As fas as we know, we were matched by the programmers. They were checking our backgrounds.

MB: We didn’t chose each other, it was all given.

You had to make some important joint decisions, such as shooting black & white.

GGL: There wasn’t much talk about it. We both had a feeling that this was the way the film should be done. Only later we started also understanding the possibilities it was offering us. We were looking for a strong contrast, harsh with some texture from the image. It was more about the intuition than the specific rational decision.

Why did you choose Porto as the setting?

GGL: The proposal was to shoot in Porto, so that wasn’t our idea.

You layered your film very subtly. It is on the one hand about the city getting gentrified, and the tough decisions people have to take. On the other, it is also a story about two women who are brave enough to stay faithful to themselves.

MB: It all began with our discussions about expressing emotions, but then we slowly began to realize that we had a very complex story that is quite fitting for a feature film. That is why we settled for a different idea: showing a segment of life of the main character Clara, her emotions and dilemmas.

You approached passion and sensuality with elegance. The only erotic scene in the movie is done in such a manner, that there is nothing unpleasant or voyeuristic about it, and it looks very genuine.

MB: It was the scene which we rehearsed the most actually. We put a lot of effort to shoot it correctly, and to create a safe environment for actresses. We had a written scene which we had to re-write together, which was happening during the rehearsals. Also, the cameras rolled during those rehearsals, and we would set something up in front of it. Eventually, the precise position of the camera was clear when we had the choreography figured. Regarding the passion you addressed, what interested us was how the eroticism has the power to delute frontiers, and make us doubt ourselves adn the others.

GGL: I remember that once Mariana showed me a text called “The Power of Erotic” and we were discussing a lot about how to express that. For instance, Raquel, the woman working on the boat feels more connected to her own desires and emotions through sex. She is trying to convince Clara to board the ship with her and leave everything behind: sell the café and give up fighting what seems to be an inevitable gentrification of the habrour. Clara’s sexuality is in a completely different place, which also is clearly defined in the dialogue. It was also a very political choice to use eroticism to express certain relationship mechanisms. There is an internal negotiation between the desire and what Clara can do. What bares more weight: her desires and her love, or this world that she belongs to? We didn’t want to give an answer to that.

The film has a strong documentary feel, even though it’s clearly scripted and acted.

MB: It’s our background, and that’s the way we work.

GGL: Yes, but we also are around the world, and we really wanted to observe and allow their faces and bodies to melt with the environment that defines them. Likewise, people at the bar are all authentic. The bearded fisherman is a natural born actor.

MB: There was a lot of cincerity in things he was saying although he absolutely don’t represent that opinion in real life.

GGL: Of course, everything was written, but the work that we did, and the whole preparations made it all look genuine.

MB: Actually, all of the fishermen we met were pretty much against the gentrification, but we needed someone who would be the devil, and Joaquim Castro who played Caveirinha had the capacity to embody the other side.

GGL: Also, we wanted to find the scene where we also could catch something quotidian, because as we know, unlike the photography in our film, nothing in life is black and white. One day when we went to that bar to discuss with them that we didn’t necessarily want to film present their sentiment towards the gentrification, but the possibility that they would get tired of their hard work one day.

MB: I will go back to comment about the documentary feel you get while watching Seagulls Cut Through The Sky. We documented a place that is going to dissapear. It is not a real bar, it’s a venue where people are coming to eat and that will soon be torn down in few years. In a sense, it’s a documentation of this place.

My final question goes to Guillermo. Spain and Portugal might be neighbouring countries, but it is still a ‘foreign setting’. How was it for you to indulge into the fragile world of the Porto’s labour and work with it?

First of all, my mother comes from Galicia which is very close to Portugal and my home is actually there. Beside of that, I trully believe that the geopolitical borders sometimes are just the concept and that we filmmakers had to meet, get to know each other and exchange experiences, but more through our thoughts about the cinema, through asking questions, the momentum we are living. That made it easy for me to approach the place, and to be comfortable filming in Mariana’s place.