Reflections 9

Autumn is my favourite season; red and yellow leaves falling, pumpkins and pumpkin spice, cold nights drawing in, golden sunlight still flooding in through my window, and a flurry of film festivals to warm the cockles (LFF, Uppsala Internationella Kortfilmfestival, Kurzfilmtage Winterthur). This time last year, my iPhone reminds me, I was taking crisp morning walks to look at the leaves and take in the glorious many species of trees in Uppsala, a city in possession of more charm and style than it has any business with. Home to Ingmar Bergman as a boy, its historic cinema, Slottsbiografen (dating back to 1914, still with its original wooden seats and hand-painted wall mural), stole my heart, which was then warmed by the people and spirit of the city’s short film festival.

Bergman aside, Slottsbiografen had such a profound effect on me that I have (countless times) since setting foot in and placing cine-bum-on-seat inside, fantasised about moving to Uppsala and running the single-screen beauty in my twilight years – I’d screen mostly repertory titles outside of the festival month. But, in reality, I have not even visited a cinema since early March. For someone who would visit cinemas with a frequency of somewhere between multiple times daily (during festivals) and at least as often as weekly (during the busiest of down times), I am beginning to wonder if it’s even possible that I still love it. I mean, I know I do, but, also, how can I if it’s not living? A distant memory, a literal past time and, albeit begrudgingly, something it appears I can now live without.

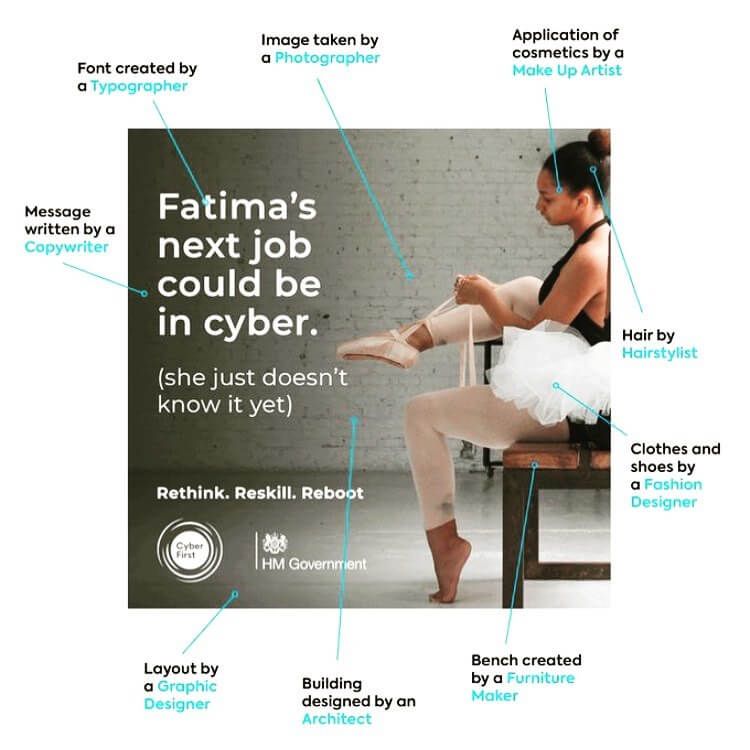

In the face of mass unemployment and the (admittedly slow) collapse of various industries, the British government has told us all to retrain and reskill. Woefully, they chose the arts as a leader target and a woman of colour to speak down to in their example of how we might all move from our once valued sector of arts into the future world of cyber (Twitter was awash with questions). And I am left, now, wondering if I ought to forget my future fantasies about running the likes of the Slottsbiografen and, worse still, just let go of a previous lifestyle of cinema-going altogether.

That may sound dramatic, but it’s almost eight months since I visited a cinema, and I have never, not since first visiting a cinema in my childhood, gone such a stretch of time between drinking in the big screen experience. Even as a poor student, I could come up with the few quid it took to see something at the then slightly run down and therefore more affordable Renoir in Russell Square, or Prince Charles Cinema in Leicester Square. Now I watch screeners via Google Chromecast on my decent but relatively disappointing TV, wondering what the carefully designed sound mix might be like cranked up to the intended volume and mix in Dolby Atmos 7, or even 5.1 surround. My crisis of cinema experience comes just as Celluloid Junkie have published their global findings, “CJ Analysis: The Number of COVID-19 Outbreaks Traced to Cinemas is Zero”.

While encouraging for the industry and overwhelmingly good as far as concerns the contemporary spate of news, it also makes me wonder why I haven’t – and might not for a while yet – visit a cinema. And, if I’m honest, it’s not just about the risks. I love the cinema experience. But what I love doesn’t really exist right now. What I love is the catharsis that comes with surrendering my mind and body to the screen via my eyes and ears. And to be embodied in that experience, I believe I need to be completely relaxed and at ease, something that the current experience of life literally anywhere outside of my home does not allow. It’s personal, of course, but for me, wearing a mask, sanitising my hands, and keeping my distance mean some of my favourite things about cinema-going can’t happen: finding friends in the auditorium by chance, hugging and having drinks with them after the film, (very quietly) eating snacks during the ads and trailers, feeling the shared held tension or atmosphere as I hold my breath, gasp, sigh, giggle, weep, or exhale with whatever’s going on, in the room and on the screen. Does this mean I love the cinema experience more or less than I think I do?

At home, I am unable to replicate my auditorium-led undivided attention to the screen: I can almost always hear the dishwasher or the washing machine, text messages catch my attention (even though I know I should just put my phone away), I constantly get up to fetch snacks and make cups of tea because no one cares if I sit still – least of all me – and, perhaps most surprisingly, I am vocal at home. I literally respond to the screen. If a character or a camera angle annoys me, I’ll shout about it, much to my co-habiting partner’s chagrin. And recently, it’s become almost unbearable for us both.

What I’m saying is that my home is not equipped for the depth of emotions cinema enables – or maybe asks – me to experience. As a space, my home is already busting beyond its ability in holding my everyday life. It can’t also provide me with the freedom I need to feel things that I don’t know how to anticipate let alone experience.

Of everything I saw at this year’s virtual LFF, Ken Fero’s Ultraviolence (2020) is the one that reminded me what else – aside from superior sound and image – the cinema experience is made for. A long-awaited follow up to his Injustice (2002), Ultraviolence continues his examination of “deaths in police custody” – i.e. state sanctioned murders in the UK. From the very second it started, it was intense. Fero begins with a quote from Chris Marker; he is not fucking around. What he does next is present the painful truth of racism, systemic and deliberate, and the ultraviolence that is so-called law and order in the UK.

I knew these truths before watching the documentary. It is not shocking, nor is it unbelievable. Instead, it is painful because it is simply true. I live in a country where you are not only allowed, but actively encouraged and protected – sometimes decorated – to kill people, and where you can continue to be paid by the state and the people for enacting this violence and hate against specific groups of people – largely, Black people, and people of colour. That is Britain. And not just the “then” of when a documentary depicts, but now, too. And always. It is the most British thing there is. Sanctioned violence, overt racism, hate, and, where possible, collusion to make sure it passes without accountability.

The film is not really ‘cinematic’, in that it uses mostly stock television and CCTV footage that will not benefit from a higher resolution file, brighter lamp, or full Scope ratio. And, conversely, to have the effect and impact it deserves, the doc really needs to play on TV in every British home. But we all know that will never happen. Though the title of this article is a bit rich (“Ultraviolence: the shocking, brutal film about deaths in police custody” – please, exactly who at this historic juncture is ‘shocked’ that white people are killing Black people?), Simon Hattenstone, writing for The Guardian, is right in pointing out how Britain will not face up to itself, “As he [Fero] says today, no broadcaster would touch him after Injustice.”

This comes just as our government have decided – during Black History Month – that “Teaching white privilege as uncontested fact is illegal”. Illegal.

Not that the kids are worried about the ideology they’re subject to at school; it’s difficult to dismantle insidious ideology when you’re starving (“Tory MPs Vote Down Labour Motion To Implement Marcus Rashford Free School Meals Plan” – yes, 322 conservative MPs, including Vicky Ford, the children’s minister and Jo Gideon, who is a trustee of the charity Feeding Britain, voted against a campaign to feed poor, starving children.)

Shouting, crying, and occasionally wailing at the contemporary resonance and injustice of it all, I turned my living room into a space filled with rage. But I didn’t know what to do with it. There was no one to talk to after the film about what we might do with that anger and pain. And, at home, I suppose I just couldn’t turn it back into hope – despite Fero’s attempt to channel it that way, ending with the sounds of a baby and the notion that, “Endless brutality requires endless resistance.” It’s the endlessness that worries me.

Right now, Ultraviolence has only screened at LFF, and it is not listed (at the time of writing) as showing anywhere else. It is extremely unlikely that any television station will pick it up, after Injustice saw the Police Federation silence Fero by threatening to sue anyone who showed the film. As Hattenstone writes, “The TV networks were terrified of the consequences… scared off by libel lawyers.”

Perhaps our pain, anger, and even our hope or catharsis is all that the state have not yet taken from us. Which is why we need public spaces, dedicated to holding those emotions.

But there is some good news. The UK government has also just announced the recipients of its Cultural Recovery Fund and launched it into the Twittersphere with #HereForCulture. With a major cinema chain – Cineworld and their subsidiaries including Picturehouse Films and Picturehouse Cinemas – closed until further notice, and with Odeon cinemas closing some of their sites and reducing operating hours in others, owing to major studio decisions to delay tentpole releases like No Time to Die (now slated for 2021), the announcement of the fund meant a great deal to the sector’s independent counterpart. Still, I can’t help but think that a lot of the press coverage around these events waded so heavily through hyperbole that it forgot entirely how Cineworld was financially unviable before Covid, as Jim Armitage, writing for The Evening Standard outlines, “Even without the debts it would run up from the Cineplex transaction, its net debt is now running at $8.19 billion, compared to its total asset value of $1.19 billion.” Not to mention that Picturehouse Cinemas were embroiled in years of controversy around wrongful dismissal of union reps fighting for the living wage.

Much like Picturehouse and its parent company Cineworld, the first wave of the recession (amid our second wave of the virus) has let the floodgates open on other companies whose practices are less than ethical. One major recipient of the Cultural Recovery Fund is Secret Cinema, who run immersive film events at a premium price (think upwards of £50). They have been serially outed on Twitter for alleged dodgy employment practices and for yet another unviable cinema model (they declared a financial loss of £2.9m in 2019, which they don’t address in their statement). One can’t help but wonder how the UK government decides who retrains for cyber and who gets to forge on into the brave new normal.

If UK cinemas were trees then their leaves have already turned, and now they are starting to fall.

I long for Uppsala, its gorgeous trees, and continue to fantasise about running its stunning, historic, single-screen cinema, Slottsbiografen.

2020-10-28 @ 16:28

Great article. Wanted to let you know about AMPLIFY! collaborative virtual film festival, four UK festivals Cambridge, Bath, Bristol and Cornwall coming together in these difficult times supported by BFI, National Lottery with media partners Scala. Amazing new cinema blasting into our fronts rooms from 6-22 November with stunning features, lots of premiers, hot docs, Q&As, free shorts programme and Young Jurors initiative. Check us out at http://www.amplifyfilm.org.uk and on social media we have set up a film club AMPLIFY! film club on FB (https://www.facebook.com/groups/amplifyfilmclub) to get the conversations going while we can’t have those chats in the bar at the cinema. Just secured our last fab films today which will join the programme ASIA,

CODED BIAS, VEINS OF THE WORLD / DIE ADERN DER WELT and SCHOOLGIRLS / LAS NIÑAS adding to other highlights including FALLING Vigo Mortensen’s directorial debut, INTERDEPENDENCE – A unique and captivating anthology of 11 short films that humanise the climate crisis with Live Q&A, WAXWORKS one of the highlights of German Expressionist horror and THE MOLE AGENT an 80 year old goes undercover in a care home. If you want a press pass and would like to write about us do get in touch