Remembering Robert Frank

Robert Frank died in September this year. In the mid 1950s, traveling on a Guggenheim fellowship, he took 27,000 photographs while crossing America. He distilled a book of 81 photographs out of 800 rolls of film and called it The Americans. It made diners, off-beaten tracks and cool cowboys on city pavement popular. And almost a dream. Although nothing was as it appears. If it wasn’t for his monograph The Americans, an average European who dreams of vast Prairies, endless road trips of self-discovery, of getting lost, would have a harder time imagining how that trip might actually look.

He’s the artist who became a journalist soon to become a filmmaker , on temporary assignment to our collective dreams, the “walking contradiction, partly truth and partly fiction,” He was half foreign, half immigrant; half genius, half savant and a pure component of the adulterated profane. One of the original high art low-lives, it was in opposites where he truly thrived. He made what the amateur couldn’t and the professional wouldn’t, and created something the critics miss and mass audiences know but can’t explain. Like Bob Dylan, he was an outsider who became the shrewd observer lauded for being a sage at the heart of a nation’s center, and then refused the position to forge on, changing himself continually as a means to convey the simplest of truths about us again and again in new ways.

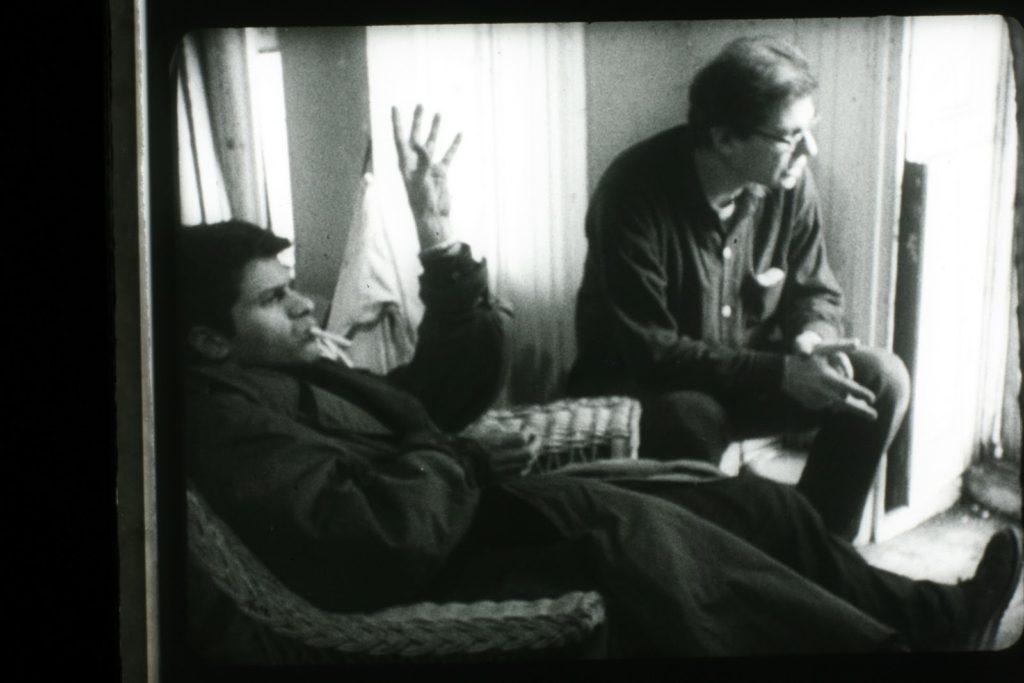

Coined often as a “narrative photographer,” The Americans has also been called a visual poem. But the poems often have hidden meanings. “When people look at my pictures I want them to feel the way they do when they want to read a line of a poem twice,” Frank said of his works. But look twice quickly, because he’s already moved on. By the time one of the most iconic books of still photos came out in the United States Frank had already set down his Leica and picked up a 16mm Bolex. Chasing the moving image as if to set the static one free again, he began in 1959 with several notable short, black and white experimental films. His first, titled Pull My Daisy, was narrated and written by Jack Kerouac but also starred other prominent Beat Generation members such as Alan Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and Peter Orlovsky, seen congregating together in their New York haunts, speaking their jazz-like philosophy on what seems like a randomly selected day.

He mixed fiction and reality with incredible ease. The easy blend of professionals and amateurs is interesting in his 1969 feature ‘Me and My Brother’ where young Christopher Walken played Peter Orlovsky‘s mentally ill brother Julius, who wandered out of the film partway into the shooting . Frank co-wrote Me and My Brother together with Sam Shepard, ostensibly a documentary about Peter Orlovsky and his mentally ill brother Julius on a book tour, the film eventually slides imperceptibly into fiction.

OK End Here from 1963 for some critics meant parting with a form although it was his only third short film and/or faux Antonioni, it’s an ‘ennui dans le couple’ in a course of one day from waking up to having dinner with friends and coming back to the apartment. In it, we follow Sue Mingus ( Charles Mingus late wife ) and Martin LaSalle (Bresson’s Pickpocket) through their regular day in an upper class New York apartment. They slog through the apartment, carrying out mundane operations intersecting with moments of drifting and contemplation over their love life and state of things. They are briefly interrupted by visit from his ex-girlfriend accompanied with her new boyfriend, a rather tedious and overachieving character who presumes he can advise LaSalle on how to live life.

Both Sue and Martin don’t really know what they want out of life or each other. The inertia in modern relationships was similarly examined by many filmmakers such as John Cassavetes’ Woman Under the Influence or Godard’s Contempt to name few obvious examples.

Robert Frank mixes documentary scenes with more theatrical performances. The scenes in the restaurant where the couple meet their friends and foes clearly depict these tendencies. One never knows if the whole set up is staged and preconceived. When a random lady sitting next to the couple suddenly joins them and reads a letter from her lover to Sue, asking for help in understanding it, Sue quickly loses interest and this lady realizes they don’t care about her. Was she a part of a staged scene or didn’t she know she was being filmed?

About Me: Musical from 1971, was planned as a musical study of indigenous American music, but turned out to be a Robert Frank musical about his own life. Through symbols and questions he examines his own life and work. Frank himself is inexplicably played by Lynn Reyner, dressed in an improvised Roman toga made of bed sheets. She walks through a seedy apartment inhabited by various friends and visitors. He/she examines Frank’s life symbolically, questioning his work (and what response from others?) The audience are his friends and random visitors. The blend of ‘known’ and less known characters, such as the appearance of Wavy Gravy with Allan Ginsberg adds to the mix.

It’s Frank beatnik mood at his best, fully embracing the boho lifestyle – at least for the time being.

His short mixes of documentaries and loose narrative, as in his only feature film Candy Mountain which he co-wrote w Rudy Wurlitzer, are not as sensational as one would think. It’s more of a testament to the beginning of an end. Is it a road, a tour, a relationship or life itself? It’s the end of a road. It’s the end of an American road. Frank moved to the USA in 1949 from ‘neutral’ Switzerland in the beginning of the aftermath of WWII. He landed a job at Harper Bazaar and was doing fashion photography until he received a Guggenheim scholarship which allowed him to partake in the two-year trip across the country which resulted in those 80 images. The critics didn’t expect seedy imagery of raw street life, plagued by racism and newfound consumerism. They also show the profound simplicity of everyday life on the streets, in the parks, diners and restaurant and random corners.

This radical approach paved their path for the likes of Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander.

As Jack Kerouac said, Frank ‘got eyes’. He did his best work by spotting details not immediately visible to others. He showed and possibly made ‘American’ everything we today consider very American: jukeboxes , flags blowing in the wind, cowboys and diners, cars with palm tree background.

Things get dated quickly in our culture. Today even more so than when Frank was active. But he captured and created a time capsule with his book and also with his films, the lesser known ones mentioned in this short tribute.

They are all evidence of a certain time, a continuous search and hope for a freedom of expression, the beauty of the ‘outsider-ness’, seizing the moment and daring to be different in a homogeneous culture. Essentially a foreigner on an assignment, Frank single- handedly created an ‘American identity’ in a time when official American political power was trying to purify the society of ‘foreign influence’ and/or ‘subversive elements’.

2025-05-13 @ 21:00

The only purpose of this comment is verify if it is working to leave comments.