In conversation with Mario Macedo and Dornaz Hajiha, the helmers of “Maria”

Dornaz Hajiha holds a Bachelor of Arts in Graphic Design degree from Al Zahra University, Tehran. Before plundging into the world of filmmaking, she worked as a photographer and graphic designer. Hajiha participated in workshops by Asghar Farhadi, and in 2013 she begun her studies in Film Production at London Film School, where she completed her MA and graduated with distinction in 2015. Her shorts Marziyeh (2019) and Marlon (2017), travelled the international film festivals and brought her two important awards. Her debut feature film Like A Fish On The Moon had its world premiere in Proxima Competition of 56th Karlovy Vary last year, and is still making the festival rounds. Hajiha is working on her second feature called Diaphanous, that won a Production award at Torino feature lab, and got selected at APM 2022, Busan International Film Festival.

Mario Macedo graduated in Sound and Image at Portuguese Catholic University of Porto (UCP). He is one of the founding members of a Copenhagen based 73collective, comprising of young directors focused on highly personal projects. His short documentary Maria sem Pescado (2016), which world- premiered at DocLisboa, was awarded National Grand Prix at FEST. In 2018, Macedo completed his documentary trilogy with ‘A Volta da Revolta’, and three years after his first fiction short Terceiro Turno (2021) premiered at Curtas Vila do Conde IFF Competition, where it won Best Director. He’s currently working on his 1st fiction feature The Robbery.

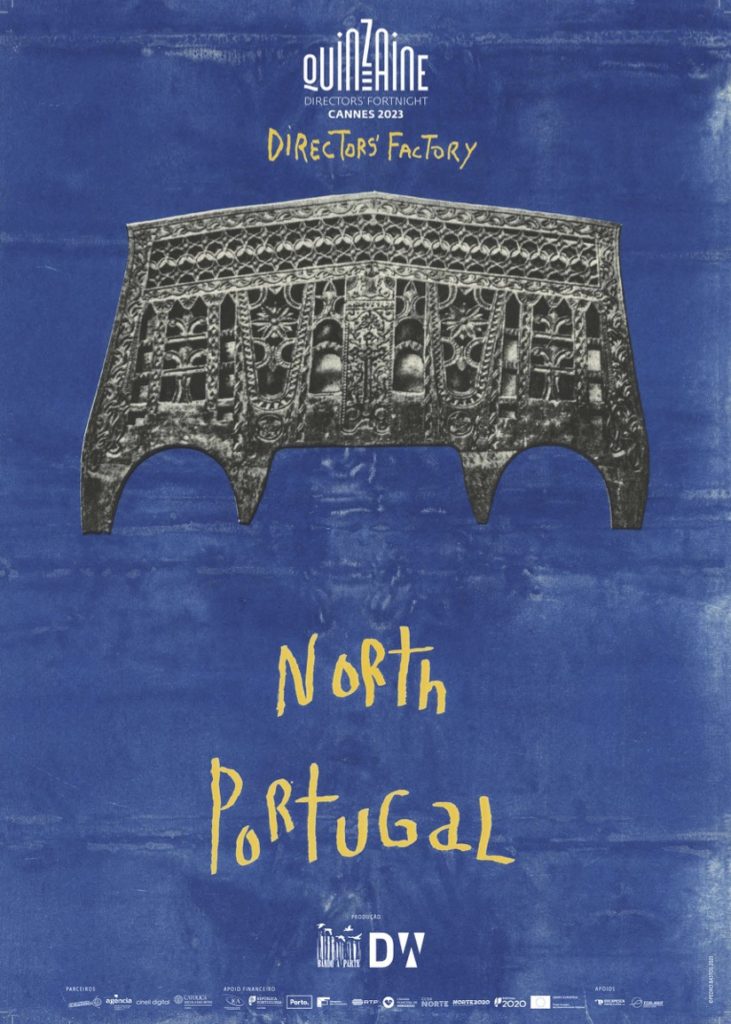

A day after the world premiere of their joint film project Maria that screened along two other shorts under the joint name Director’s Factory: North Portugal on May 17 in Cannes, we set down with the two helmers to talk about their collaboration, and experiences during a rather intense shooting period.

The Factory program opens Director’s Fortnight section in Cannes since 2013. The project was halted for a couple of years due to the pandemic, to be resurrected again in the festival’s 76th edition. Now back to life, Factory focuses on North Portugal with three short films done by mixed doubles consisting of young Portuguese filmmakers from the region, paired with their colleagues from Iran, Israel and Spain.

You entered the Factory project which is supervised by the legendary Portuguese actress Leonor Silveira. Did you get a chance to meet her and get an advice?

MM: She was part of the selection, and at one point we thought of casting her as Maria in our film, but because she was one of our selectors, she didn’t want to get involved. Sadly, we didn’t get to meet her, although we tried it. She was into it, but said it would be wrong accepting the part considering her role in the project.

Did you already have a clear ideas about the cast when you started developing the film?

DH: It was a proper casting process, but it wasn’t an usual one, at least for me, because I was away and following the process online. Mario would do the main job, and send me the videos and pictures to take a look at them. That is how we were selecting the actors.

MM: Lots of the casting was based on our intuition, because we were making a film against the clock. There was no time to stop and think too much. To me, that was the biggest lesson: without enough time, you had to rely on your gut feeling, but everything turned to the best. We found the actors who proved to be the right ones. In the end, everything fellt wholesome. It was an interesting process, and we were closely collaborating with an agency from Northern Portugal. We wanted the actors from the region only.

DH: We only had one rehearsal with all of them. When I finally got there, and when I got to know them, I only had one week. I can say that the official rehearsal had to work purely based on our instincts.

Knowing that both of you have already made a number of movies, both short and feature, how difficult was it to step into an unknown territory of co-directing a film in a very short period of time?

MM: Nowhere as easy as one could think. I actually did many films as a co-director with the difference that I knew the people I worked with. In this sense, both Dornaz and I went, metaphorically speaking, on a blind date.

DH: For me it was the first time that I co-directed a movie, and it wasn’t that easy for me to let go. On the other hand, that was a challenge that I enjoyed, and I am especially proud of the results. When I look at the work we’ve done, I think it went great. We really tried to find the best way of communication, and it wasn’t only about that. The thing that I liked about us is that if there was a discussion, it was for the sake of art, and the quality of the film. There was never a question of egos, because in a sense, Director’s Factory project is about breaking egos. I would say that we were trying to find the best vision for the film. It wasn’t easy, but the outcome is good.

Your film is based on a well penned script, and the story is set up in a very masculine, patriarchal environment. It also feels very personal, and my question is if you had an insider knowledge of a middle-scale family business.

DH: Both of us have experienced the burden of patriarchy.

MM: I actually come from the north of Portugal, more precisely from a small town that is heavily industrialized, and my own family has a small factory. I could see how the family relationships look like in a work space. For us it was an interesting location, also image- and sound-wise because there are parallels to the heavy weight of the patriarchy and religion. Religion actually makes the patriarchy even heavier, and that world looks so out of hope, gruesome and blue.

Not that you mentioned religion, the film ends by a powerful mystical scene.

DH: I would like to return to your comment about the male aggression. You have those men and women spending time together in a very loud, violent environment. Violence is in the air, and apart from that, women trapped inside are suffocating from overdose of masculinity. Having a middle-aged woman in this space, someone who wants to break free from the aggression, became our main focus. Apart from that edning which you called “exit”, I could relate to the white light that comes and grabs not only the main character and the confessional, but it swallows everything. The whole screen turns white instead of black.

MM: Symbolically, the angelic song stands in contrast to the factory setting. We wanted to express that women like Maria are everywhere. Religion doesn’t allow women to be free, so we played with that. At the end, Maria is the only one who takes a step towards something that could bring her happiness, and in the end, because we are so brainwashed through our upbringing, Catholicism and the concept of guilt, and what does Maria do? She goes to confess. It’s up to the spectator to decide where that leads her.

DH: Confession comes from guilt, and I can say that I came to this world constantly feeling guilty, as many women do without even knowing why.

MM: Regrading the Chatolicism, I must say that I as a man, although much more privileged in that sense, still carry ghosts and skeletons of Chatolicism. I never ceased questioning myself, nor thinking that I should do things differently. For me it was important that our main character, no matter how shallow, her little steps are, she returns to the place of ultimate guilt – the church. This can be interpreted as the sense of guilt, but it could also be something else.

Courtesy of Quinzaine des réalisateurs